Share

The Dangin Effect

Retouching, like polaroid, is in the the air. There’s an illuminating profile by Lauren Collins of famed retoucher Pascal Dangin in the current N...

Retouching, like polaroid, is in the the air. There’s an illuminating profile by Lauren Collins of famed retoucher Pascal Dangin in the current New Yorker; Dangin is the owner of Box Studios and works with all the big names in fashion editorial: Vanity Fair, W, Harper‘s Bazaar, Allure, French Vogue, Italian Vogue, V, and the Times Magazine. Not to mention a laundry list of a-list photographers, including Annie

Leibovitz, Steven Meisel, Craig McDean, Mario Sorrenti, Inez van

Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia.

This seemed fairly straight-ahead; interesting, but known, right? Obviously everything is retouched these days. But this paragraph gave me pause:

“The walls of the third-floor meeting room at Dangin’s headquarters, on

West Fourteenth Street, hold magnets in the manner of a refrigerator

door. One afternoon in November, grease pencils, in the colors of the

rainbow, were stuck, by magnets, to one wall. Nearby, several of

Dangin’s assistants were hanging a blueprint–a scaled rendition of the

Petit Palais museum, in Paris, where, in September, Patrick

Demarchelier will have a retrospective. Dangin was designing the

exhibit, from the pictures (many of which he would retouch) and their

frames down to the traffic-flow patterns of the museumgoers who would

look at them. Dangin would do all of the printing. He was also

publishing a companion monograph.”

I didn’t quite realize that retouchers were being used to such an extent in the fine art world, for gallery and museum exhibits. I thought the digital c-print was the new frontier; I suppose I’ve been naive. How much of this fine art imagery is the product of Dangin? The great PL diCorcia is quoted in the article:

- “‘Pascal is no longer on pimple patrol,’ Philip-Lorca diCorcia told me. ‘He has lots of well-trained pimple removers. He’s kind of free to hold

the hand of his many temperamental photographers.’ People hire Dangin, in the broadest sense, for the assurance that

behind every abstruse technical step there will be an artistic

intention. ‘Technology is in many respects mechanical, but somebody’s

got to run the machine,’ diCorcia said. “And even with a program that

comes on a disk there are a lot of subtleties. Pascal is tireless in

exploiting all the capabilities of the technology and even possibly

creating some new capabilities.’ “

Ofer, at Horses Think, has interesting commentary about his interaction with Dangin creations in the art world, when he went to see a Guy Bourdin exhibition at Pace MacGill a few years back:

- “From what I could gather, there was quite a bit of work to do in

order to get the colors to pop the way Bourdin meant them to. I’m not

sure about what went into scanning and printing them but you could tell

that someone worked extremely hard to make them as gorgeous and

meticulous as they were.

For comparison, see the current Marvin E. Newman

exhibition at Silverstein Gallery consisting of recently printed Inkjet

prints of vintage chromes. While I admire Mr. Newman for dedicating

himself to the newest in print technology (I was told he made the

prints himself), I really wish he could have worked with someone more

experienced on them. Not all the pictures are lacking but a whole bunch

(even visible in the Jpgs online) seem to be flat with little color and

no real blacks. I’m easily disappointed especially when I’m expecting

images to just pop off the page.”

Are some fine art images that we consider “straight” actually really manipulated? What about my favorite diCorcia Head? How can those of us making c-prints in the darkroom compete?

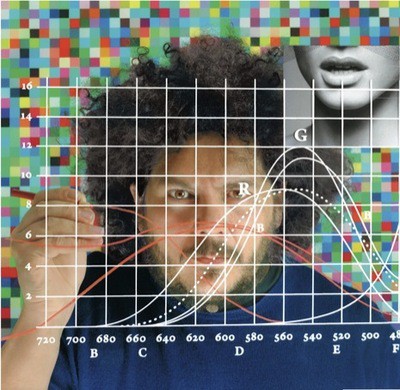

Fujicolor Crystal Archive print on Plexiglas