Share

History, Rock ‘N’ Roll and The Many Lenses of Ethan Russell

with Chris Owyoung & Ethan Russell On the eve of his closing night presentation at the Palm Springs Photo Festival, I caught up with legendary ...

with Chris Owyoung & Ethan Russell

On the eve of his closing night presentation at the Palm Springs Photo Festival, I caught up with legendary creative Ethan Russell to talk photography, video and rock’n’roll.

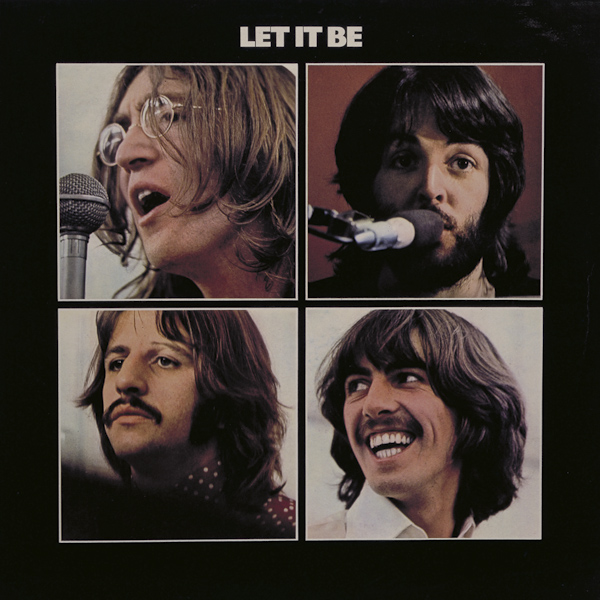

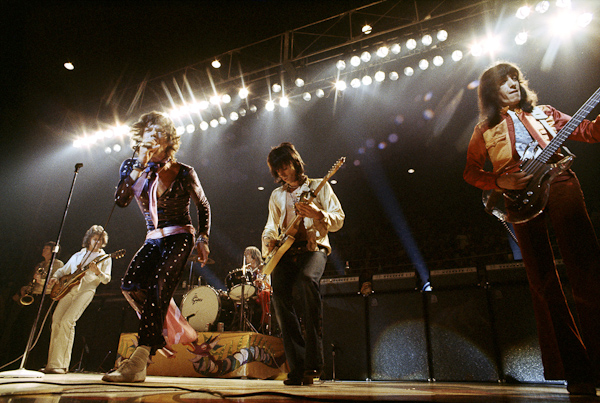

Ethan is a multi Grammy nominated photographer and film director. He is the only artist to shoot covers for The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Who. Ethan is also an award winning creative director and the author of two books, Dear Mr. Fantasy and LET IT BLEED: The Rolling Stones 1969 U.S. Tour.

PHOTOS BY ETHAN RUSSELL © APPLE CORPS LTD: Album cover for Let It Be, The Beatles twelfth and final studio album.

Chris: You’re known for capturing really honest images of extraordinary people. How did you first get started?

Ethan: The first thing “photographic” that truly affected me was The Family of Man. In retrospect I think I can say why that is. Family of Man really rests on three legs: 1) the photography, 2) its central narrative: the “family of man” and 3) the writing (the excerpt of quotations throughout the book). It is the humanism of the content that works for me, and not the photography somehow in isolation from that. And the entirety wouldn’t hold together the way it does without the really brilliant and concise collection of quotations.

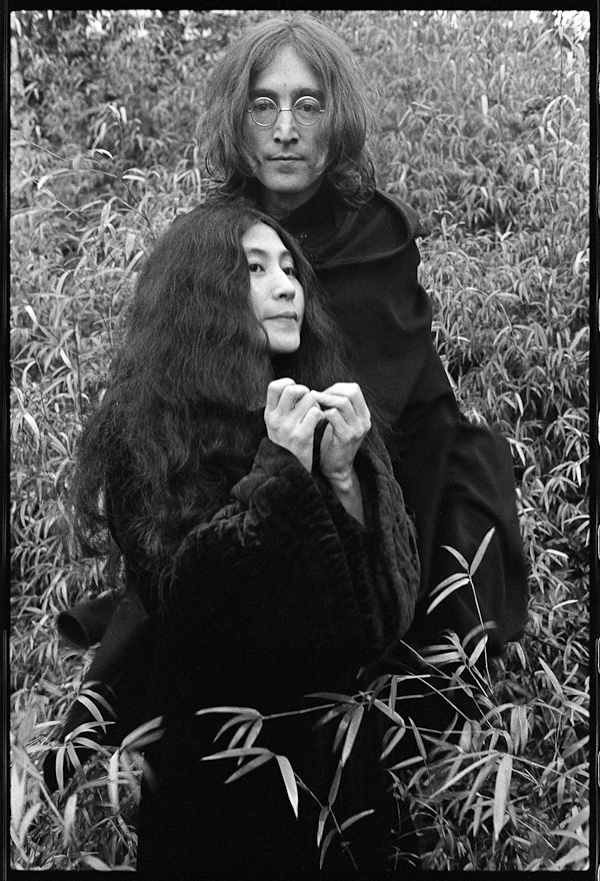

All of this really lines up with my work as an artist. It was the big human ideas of the 60s that sucked me into the music and kept me there. And when those ideas and concerns drifted from the forefront of music, I left. Sometimes I am asked who was my favorite artist (one of those kind of questions) but my answer is John Lennon and that is partly because I felt, of all of them,he didn’t lose his attention to our common humanity as the central focus. Finally, all of my books to date have been books that rely on the story and narrative equally as much as they do on my photographs. LET IT BLEED took me six years to complete because of the words and the story. I had the photos before I began.

I can be interested in a photograph for a host of reasons – form, execution, technique (in fact these elements came to hold a separate interest for me as I became better at my craft) but what really matters to me is how a photographs affects me emotionally. And that is still the case and still what I aim for in all my work as an artist. It is seeing into a person or seeing into the humanity of a moment that is the soul of it for me.

But actually becoming a photographer was something that I fell into. It wasn’t something I studied, ever, or a career I thought I might want. The first time I recall ever taking pictures was when I was seventeen. My grandmother sent me to Europe, and my grandfather gave me a camera. But when the trip was over I put the camera down.

PHOTO BY ETHAN RUSSELL. COPYRIGHT © YOKO ONO: John Lennon and Yoko Ono “Capes”

Chris: When you were starting out, how did you make sure you got noticed and, assuming things went well, how did you make sure you got paid?

Ethan: It seems many of the questions I get, especially from young photographers, are similar to yours, and I always feel somewhat badly about sharing my story since – in so many ways – it fell into my lap. But I did two things proactively: I showed up, and I showed I was interested, which I was. I was fortunate that people seemed to like me and the work. And, of course, once you’re photographing Mick Jagger, which is how I started really, then people sort of assume you know what you’re doing. I didn’t always get paid, truthfully, but most of the time. It wasn’t about money.

Chris: The idea of starting out photographing Mick Jagger seems unbelievable? How did you get that first gig?

Ethan: When I was in college (University of California at Davis) I was first an English major and then I switched to a combined major of English and Art. To the extent I had any idea what I wanted to be, it was to be a writer. That’s what I said. I first learned what an f-stop was and how to develop black and white film from my roommate who was also a writer. So from him I gained this really minimal understanding of the basics. And then the movie Blow-Up caused me to pursue photography with a little more direction – it was so sexy – and I purchased a Nikon. But at the time I was asked to photograph Mick Jagger I was working in a hospital with autistic children, and the camera was in the closet. The story is a friend of a friend came by my flat in London (I had gone to England as part of my father’s suggestion, I think to get me out of San Francisco, but that’s another story) and while he was there I showed him some of my pictures. Turns out he was a writer for Rolling Stone, then in its third issue or something, and he asked me if I wanted to photograph Jagger who he was about to interview.

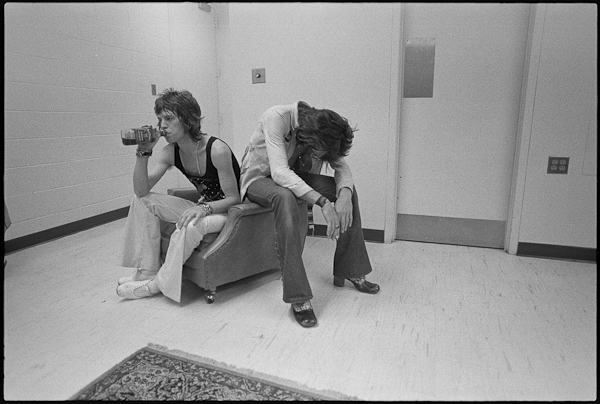

PHOTO COPYRIGHT © ETHAN RUSSELL: Mick Jagger and Keith Richards “Drink” 1972

Chris: How did you approach your early work? What has changed since then?

Ethan: Well, like I said, my skill set was minimal at best. What I had that was valuable or unique, I had as a gift, you know. The same reason, I believe, someone can hear a new melody in their head or tell almost without effort if a note is sharp or flat. I can’t! That is given to you by your Creator, you know. I had an eye – I could see, and frame, almost from the first day. I used to hunt as a child and I have recently been thinking about the parallel between what I used to do then (be patient, look closely, stand still, and then move quickly, decisively and with focus when the moment happens) and my work as a photographer, especially my early work.

But everything else was a learning curve. What’s an f-stop? Huh? How do you light? All of that was painstaking, but I learned it over time. I went from 35mm to 2 1/4 up to 8×10. And the style of shooting became more diverse. I could work in a studio or on location. You know, I honed my chops. Functionally, the biggest difference wasn’t as much technical as it was the paradigm shift from the person who was on the edges and moving invisibly to the guy that worked behind a fixed camera on a tripod and had to bring the subject out to the camera. They’re two entirely different things.

My work always was rooted in what I found interesting and I always had this interest and engagement with the singer-songwriter that would inform the way I might take an image. Quadrophenia with The Who was probably the pinnacle of that — where I worked with Pete Townshend and created an entire world to reflect what he was writing. So it’s still the same passion for music and the message of music, if you will, but since my skill set had grown as an artist I was able to tell the story in a different way. That work was entirely “built” – models, props, etc…. it was also an homage to photography I’d seen in Family of Man and early British black and white films that had affected me in college.

Chris: Evolving from taking pictures “on the edges” to art director for Quadrophenia is a huge evolution; one that many creatives have to explore. How do you go about getting the best out of your subjects?

Ethan: I don’t have a single answer. I try my hardest. And it’s not easy . I don’t have what I think of as a bag of tricks. I’m trying to see into the person or place. I like working with what’s genuine so I try and encourage that.

PHOTO COPYRIGHT © ETHAN RUSSELL: Photo from Quadrophenia, The Who

Chris: The Stones, The Beatles and The Who were already famous by the time you worked with them. Did that change how you worked? Was there anything off-limits?

Ethan: Well the concept of off-limits didn’t really apply to me because that presumes I wanted to cross limits that were set to keep me out. And I had no interest in that, which is maybe why I was allowed to be around as much as I was. I was just glad to be there. Townshend used to complain that I didn’t tell them what to do.

Chris: Did you have any idea of the weight your work would carry decades later?

Ethan: Not really. I know people that know the work tend to like it, and I’m grateful for that.

PHOTO COPYRIGHT © ETHAN RUSSELL: Cover of Who’s Next, the fifth album by The Who.

Chris: Between the three-song-limit, and the rights-grab contracts, there’s a sort of epidemic sweeping music photography right now. Is modern music photography dead?

Ethan: Oh, I’m appalled by all of it. I hate the celebrity culture, and everything it implies. It’s a sickness that infects the people both behind and in front of the camera. And the audience. Talk about empty calories.

I’m also aware that history is not being recorded – and after all these years – I think at least some of the value of my work is very much in the history it captures – and so not to allow it to be captured is a social loss. But people are so focussed on success, and success is now so defined by the celebrity lens – especially in entertainment – that the work turns into what looks to me like product photography. The subjects seem more product than people.

As for the rights grab, it ought to a) be illegal and b) photographers ought to tell them to fuck off. I do. You can’t blame the rights-grabbers if the photographer lets them. Hey, it’s free. But I have compassion and sadness for photographers trying to work today. It is a very challenging environment. Do it because it speaks to you and hold onto your rights if you can.

Is it dead? Of course I don’t know. If you define it by being able to shoot artists in arenas, maybe. But musicians don’t live in arenas all the time. I saw the same thing watching the Olympics recently when the television camera zoomed back and there must have been – seriously – 25 photographers in a pen stacked eight deep shooting from the same angle over each others shoulders. I made my blood run cold. I don’t know how you work like that. I mean, really, by the time you have HD and you can pull a frame from that for the purpose of that kind of image it does seem only a step away until it can be done robotically. It’s a sadness.

PHOTO COPYRIGHT © ETHAN RUSSELL: The Rolling Stones on stage during their 1972 tour.

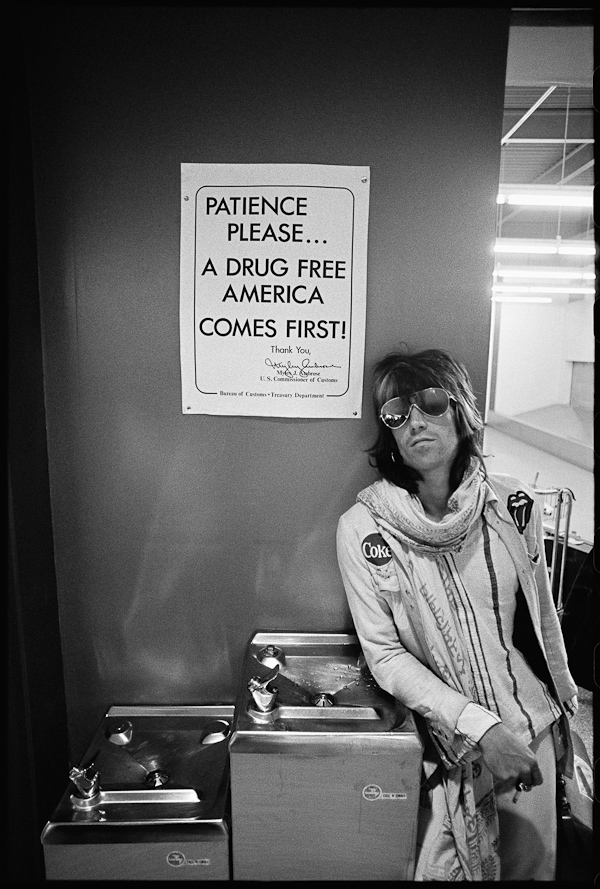

Chris: I have to admit; your photos of Keith Richards “Patience Please” and The Rolling Stones on Stage 1972 are two of my favorite music photographs of all time. How did you create those images? Is holding a camera and being there simply enough?

Ethan: Well, I’m proud of the Keith Richards’ shot because it’s truly my shot. In other words, he wasn’t standing in front of the fountain. I saw it and called him over, so if I hadn’t: no shot. Of course, he was him and wearing those clothes so you couldn’t have asked for better casting. As for the Stones on stage… thanks. I see that mostly as a technical achievement, getting five people looking decent in a frame. And of course without autofocus or any of those marvelous things the camera now helps with. As for “Is having a tricked-out camera and simply being there enough?” I nod to the title of Lance Armstrong’s book, “It’s not about the bike.” But the “Olympic” problem I described earlier is really a problem. Put that camera on a track with HD and a little dolly head and you don’t need me.

Chris: What are your favorite shots?

Ethan: While I like different types of my work for different reasons – I truly admire good studio portraiture. But if I had to choose I would say the work that is the most compelling is the work where I had the least overt influence on the situation. The early work where I’m on the edges. Certainly part of it was because I was around such legendary subjects, but it’s also true that – consciously or not – I never tried to change the situation. People are never – or very seldom – staring into my camera, and the net result is the viewer, I think, truly gets to feel like they are there.

If I had to choose a couple of prints to single out they would be John Lennon Listening to the White album and Keith Richards “Patience Please.” Both of those were shot on 35mm. There’s a lot material I like from the Let it Be sessions, too. But I have quite a few I like, in different formats and diversely executed. I think Quadrophenia is a terrific piece of work.

PHOTO COPYRIGHT © ETHAN RUSSELL: Keith Richards standing in U.S. Customs. “Patience Please”

Chris: What sort of equipment are you using now?

Ethan: Today I shoot digital: Canon and medium format digital. But I do many things today besides photography.

Chris: Speaking of things besides photography; after Quadrophenia, you drifted away from still photography and began directing motion pictures. Was the transition liberating or more difficult?

Ethan: For me, interestingly, less difficult. I loved having a group of other talented creatives to work with. I loved having focus be someone else’s problem. And so, yes, liberating. It also changes your footing with the subjects because of the more equal standing a director has with the “talent.” But the challenges were elsewhere. Especially in the major motion picture area there are such layers of nonsense that you can spend literally years without anything happening, while thinking something is happening. I did that for awhile, but I don’t have the temperament for it. I liked doing it, to be clear and did some good work. It was just that so little time was actually spent doing it as opposed to having meetings about doing it. New technologies change this equation somewhat but here, like photography, because it’s simpler and cheaper to produce, the downward pressure on price that affects the people making it is also a problem.

Chris: HD video capture is now built into almost every camera on the market. What do you think about the blurring lines between motion and still photography?

Ethan: You really have to think what is valuable about either the motion or the still photograph. It’s not the fact of it, it is the communication from it. So it’s just the expansion of the tools. The central question is still “how do you use it?” And of course, by having motion footage you don’t have a “movie,” you have motion footage.

Chris: Do you have any final words of advice to those who are following in your footsteps?

Ethan: Not overly. The important questions are what choices do you make in life? And why. And work is only one of them. It’s handy to try and include some element of service – who is this helping besides me? – since that always seems to open up opportunity. But at the end of the day my life has been of the John Lennon School of Living: “Life is what happens while you’re making other plans.”

As the closing speaker at the Palm Springs Photo Festival on April 1, Ethan will be showing excerpts from his work spanning 1968-2010. He is currently working on his third book, a speaker series based on LET IT BLEED and exhibitions in Paris and Australia.

Ethan’s website

Ethan’s PhotoShelter Archive

Let It Bleed: The Rolling Stones 1969 U.S. Tour