Share

Mike Daisey, Truthiness, and Photojournalism

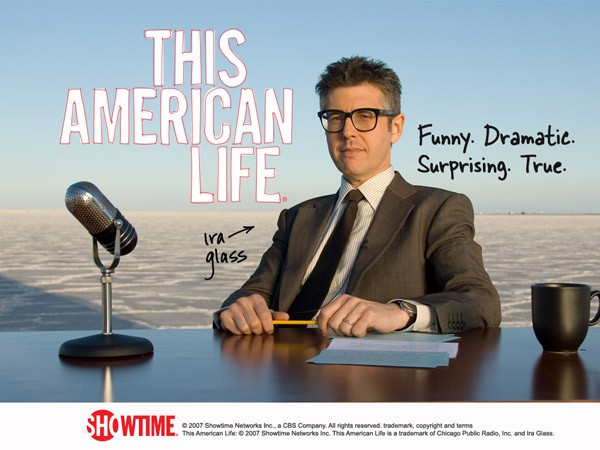

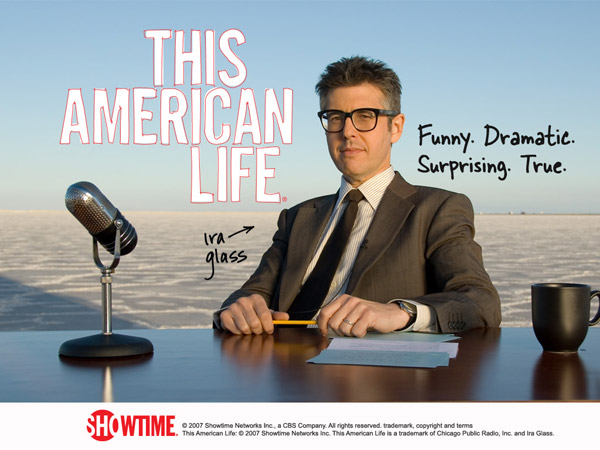

Over the weekend, the popular radio program and podcast This American Life produced an entire show’s worth of material to retract a previous ...

Over the weekend, the popular radio program and podcast This American Life produced an entire show’s worth of material to retract a previous story about Mike Daisey and his sold out, one man show, “The Agony and Ectasy of Steve Jobs”. The issue at hand was Mr. Daisey’s fabrication of events in his theatre piece under the guise of wanting to report on harsh working conditions at Foxconn, the company that produces many Apple products.

Over the weekend, the popular radio program and podcast This American Life produced an entire show’s worth of material to retract a previous story about Mike Daisey and his sold out, one man show, “The Agony and Ectasy of Steve Jobs”. The issue at hand was Mr. Daisey’s fabrication of events in his theatre piece under the guise of wanting to report on harsh working conditions at Foxconn, the company that produces many Apple products.

When I initially heard about the retraction through various news outlets, my reaction was “what’s the big deal?” I heard some quotes from Mr. Daisey proclaiming that theatre isn’t held to the same standard as journalism. I couldn’t agree more. But I was curious, so I decided to listen to the entire show.

My mind was changed.

Host Ira Glass constructed a solid argument. The producers had approached Mr. Daisey to use parts of his show for a broadcast. They asked him to ensure that what he presented was, in fact, up to journalism standards because their show is journalistic in nature. He assured them that it was so. But when they asked Mr. Daisey for his translator’s contact information (a woman named “Cathy Lee” who is portrayed in his show), he said that her cellphone number no longer worked and he couldn’t get in touch with her.

In Ira’s words, he should have “killed the story right there.”

Another reporter, Rob Schmitz, had listened to the original Daisey piece, and he immediately had many doubts surrounding the veracity of Mr. Daisey’s tale. For example, Mr. Daisey says that the guards at Foxconn had guns, but no one but the military has guns in China. A number of other issues raised red flags, so Rob decided to track down the translator. He thought the task would be difficult, but one Google search later, he found the woman (go SEO!), and found out that many of Mr. Daisey’s anecdotes were fabricated.

Mr. Daisey reluctantly admitted that parts of his show never happened. Or more specifically, they didn’t happen in his presence. He used theatrical license to appropriate stories he had heard, and represented them as his own experiences. It raised the emotional stakes in his estimation, and it made people care about the workers again after the initial news cycle of worker suicide had passed. The end result (people care!) trumped the truth (he made up stories!).

Hearing the retraction made me think about some of the conversations we’ve recently had about photojournalism, including one about photojournalism contests. Some readers commented that there is no visual truth. The use of black and white film subverts the truth. The use of lenses that compress visual information distorts the truth. The way a photographer crops, tones, or applies filters alters the truth. Many people took the position that as long as you weren’t removing or adding elements to the scene, there was no issue. A few people pointed out that Europeans have no such hang ups about Photoshopping images.

I understand and appreciate the sentiment. But it still bothers me.

Because here’s the thing: when we alter an image to heighten the gravity of the situation, we are essentially taking the same position as Mike Daisey. We’re trying to make the picture as visually appealing as possible in order to draw attention to stories we believe need to be heard. Go to Africa to report on famine, desaturate the images to make it look really arid. Go to Antarctica to capture melting icebergs, boost the blue hues. Vignette an image to really create an obvious focal point.

But when photojournalistic images become artistic through something other than composition and framing, we cross from truth to truthiness. We are saying that facts should never get in the way of a good story. We are editorializing rather than reporting. And we’re doing it on purpose, which is the worst part of it all.

A number of pundits have compared Mike Daisey to the Kony 2012 video, which went viral a few weeks ago. Convenient facts (like how the Ugandan military perpetrated many of the same atrocities as Kony) were omitted to vilify Kony. Was the net gain worth it? Maybe. The campaign raised awareness of a wanted warlord and raised money that ostensibly will be used to help some of his victims. But David Carr astutely points out in a New York Times piece, “…there is another word for news and information that comes from advocates with a vested interest: propaganda.”

Listen to the This American Life piece, and then let me know what you think.