Share

The Unsettling Future of Facial Recognition

The first time I witnessed a camera detect a face to aid the autofocus system, I was amazed. In part because the technology seemed magical and t...

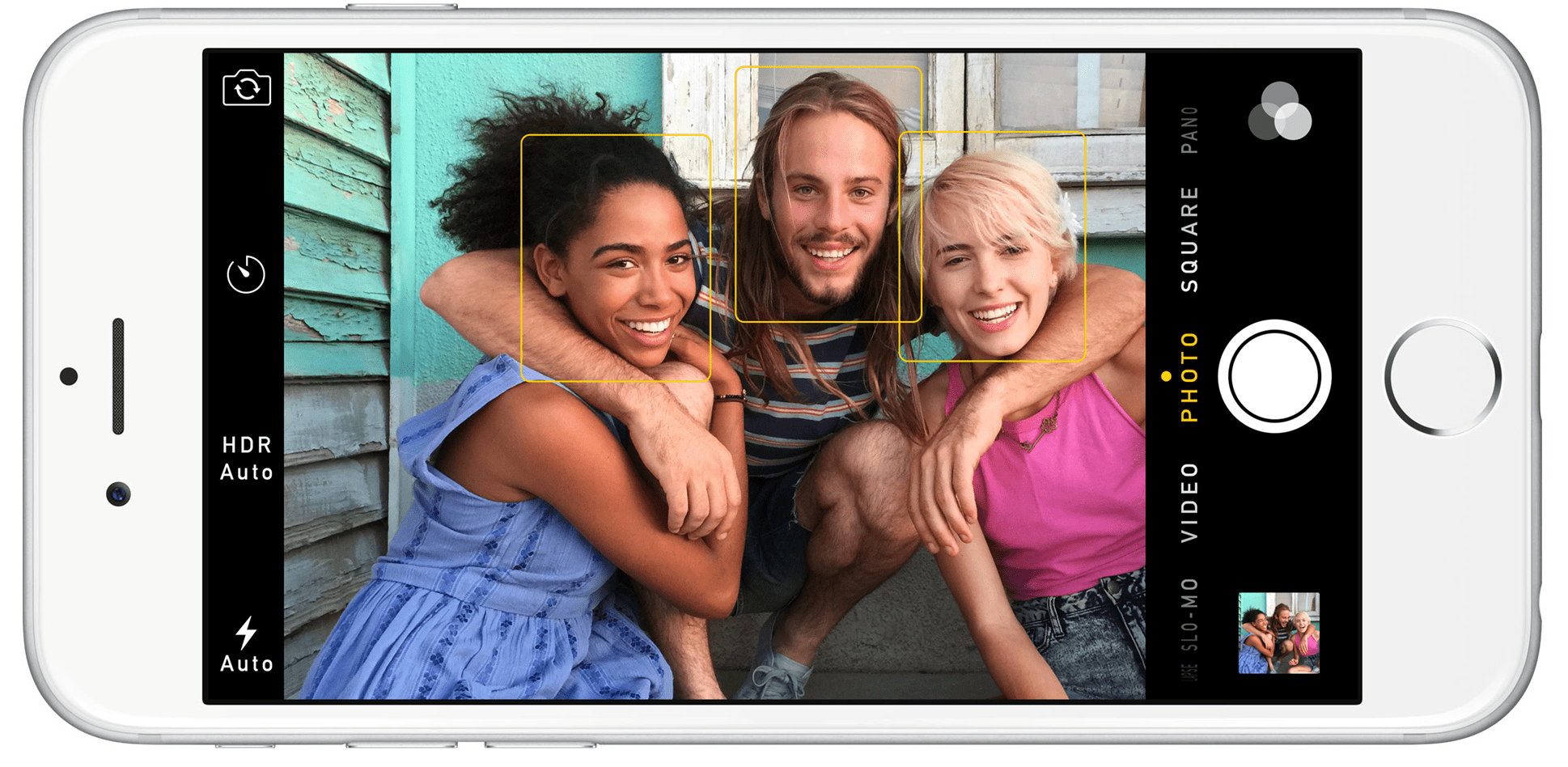

The first time I witnessed a camera detect a face to aid the autofocus system, I was amazed. In part because the technology seemed magical and the highlighted rectangle tracking faces seemed like science fiction; in part because I seem to possess a talent for taking out-of-focus photos.

The first time I used Apple Aperture’s facial recognition, I thought it was pretty novel. It wasn’t terribly accurate and it was slow (as is Lightroom’s version), but it seemed to have some utility in adding metadata to my burgeoning archive.

The first time Facebook auto-tagged my friends, I thought the future had arrived. What a great convenience and time saver for a prolific photo poster like me!

But when you stop to think about the privacy implications, the world can suddenly resemble an Orwellian, dystopian nightmare.

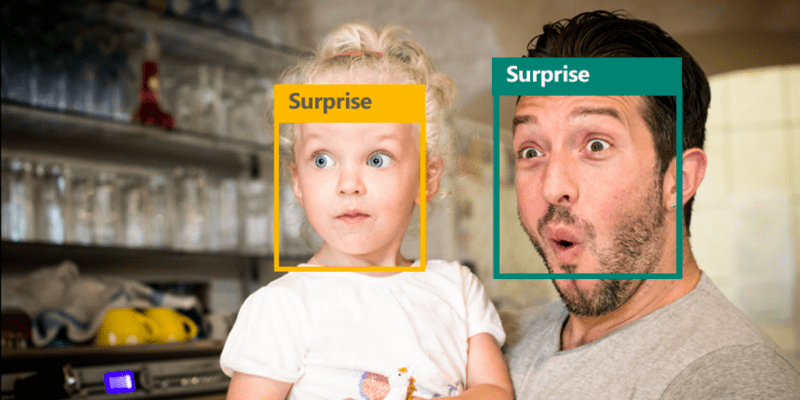

Today, Microsoft released a service that will guess your emotion from a photo. This follows their virally popular “guess my age” feature from earlier in the year, which turned out to be a pretty sneaky way to serve up ads once a user’s browser had been cookied and an age range was ostensibly tagged to that consumer. I was so caught up by the novelty of the tools (and let’s be honest, my own narcissism) to consider the privacy implications – and that’s scary.

First generation facial recognition resembled something akin to the AFIS Fingerprint system which identifies specific features like bifurcations (where one ridge splits into two) to create a unique ID. Facial detection looks for features that resemble a face, and facial recognition uses position and size of facial features to create an ID. Some cameras have detection algorithms built-in to their chips to perform this analysis.

Current generation facial recognition uses artificial intelligence machine learning. Last year, Facebook announced that their software reach near human-level accuracy, and didn’t require a frontal or near frontal view to make the identification. In fact, it could even recognize a person if their face wasn’t in the photo based on gait, hairdo and body type. Like most current AI computer vision software, the algorithms don’t require high resolution photos to perform the analysis. Microsoft only needs something larger than 36 pixels x 36 pixels. Clarifai, a start-up with some serious talent and tech, only needs 256×256.

Facebook has implemented the tech into their Moments and Messenger (Android only for the time being) apps to make it easier to send photos to your friends by automatically identifying them. This is a great convenience and it creates more “value” out of photos that might have otherwise laid dormant on your phone (or presumably in your archive). But the identification isn’t localized on your phone. It requires sending the file to the Facebook servers, which is presumably an enormous database of ever-growing facial recognition information that gets smarter and smarter over time.

Fortune reported on Churchix software which creates a database of church members, and is used not only to capture attendance, but to also prevent known criminals from attending church. The Atlantic referenced a 2014 study by Alessandro Acquisiti who found running anonymous photos from a dating site could be easily identified using Google’s reverse image search.

When the flood of biometric data available from voice command software (e.g. Siri, Cortana, Echo), facial recognition (e.g. Facebook, Microsoft), and fingerprint data is combined with other meta data from your electronic life (e.g. GPS, call data, shopping receipts, medical records, etc) – your privacy is destroyed. You can be identified nearly anywhere at any time with only the weakest of consent.

The issue has become pressing enough for the the United States Government Accountability Office to issue a report in July 2015 stating, “information collected or associated with facial recognition technology could be used, shared, or sold in ways that consumers do not understand, anticipate, or consent to.” Facial recognition is a particularly problematic form of biometric identification because it doesn’t require us to ink our fingers or speak into a microphone. The mere act of stepping out onto the street in most big cities guarantees that we will be captured by a camera, and in the future, we will be automatically identified (if it isn’t already happening).

The implications for photography are profound. How do you protect anonymity of your subjects (everyone from refugees to child beauty pageant contestant) when facial identification is so readily available? What if we’re mis-identified because of the way we stand or walk? The FBI reportedly has 52 million faces, but Facebook undoubtedly has hundreds of millions – all pre-identified, and relatively easy to link to other information like home address. (And the Snowden revelations should probably convince you that the FBI has ways to get to Facebook’s data if it really tried).

Obviously, facial recognition is here to stay. The convenience factor for consumers and the data mining potential for big business are too compelling. The erosion of privacy is unfortunately like sea level rise. We know it’s happening, we know the consequences, but we’re either powerless or unwilling to act in our best, long term interests.