Share

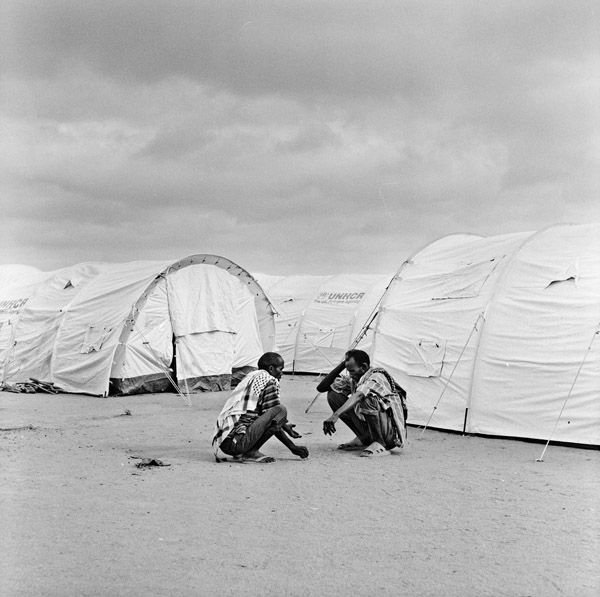

Photographing Somalian Refugees in The Dadaab Camps

Photo by Sanjit Das “It’s difficult to deal with stories like this,” says Sanjit Das about his work photographing in places like Dadaab, Keny...

“It’s difficult to deal with stories like this,” says Sanjit Das about his work photographing in places like Dadaab, Kenya – home to nearly 500,000 Somalian refugees living in aid-dependent camps. “The only way to deal with it is to disconnect and really make sure that you’re telling the story. It’s your job as a photographer to understand the bigger issue, and to chronicle it and package it as a photograph.”

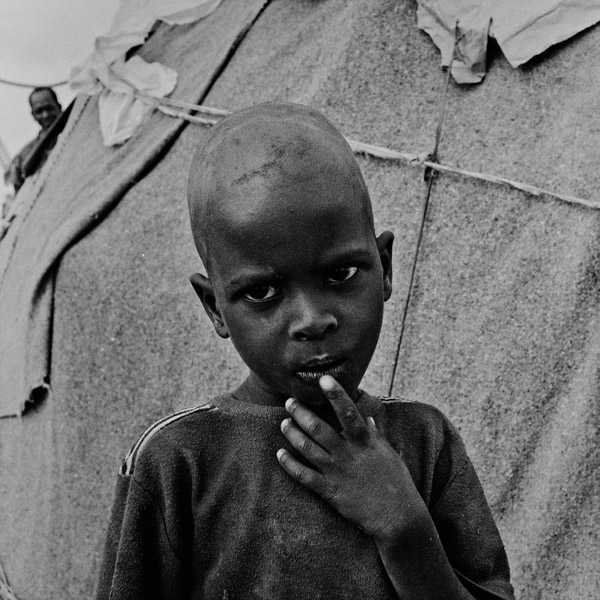

Sanjit isn’t the first social documentary photographer to feel or even speak about his work this way. One look at his images of utterly emaciated figures and one is overcome with emotion – painstaking sadness, shock, and perhaps even guilt.

But as a professional photographer, Sanjit’s job is to merely observe, not participate in the aid. “I’m not an activist,” he says. “I’m a photojournalist. I’ve learned how to separate myself from what I photograph. Of course it’s difficult – I’m only human and I want to help, but the disconnect is actually important to deliver good photos. And that’s why you’re there in the first place.”

Sanjit worries that this detached approach sheds him in a negative and perhaps inhuman light. “I’ve heard such heartbreaking stories to the point where I’ve become somewhat of a stone-hearted man. It all starts to affect you less as do more work in situations like this. It’s emotionally draining, but I think the bigger point is that these stories need to be told – it’s the responsibility of journalism.”

For that reason, Sanjit works almost exclusively on stories that he thinks need to be brought to light and will have a profound impact on people. He lives between India and Malaysia, and travels all over Southeast Asia, India, and Africa for work. Sanjit is represented by Panos Pictures in the UK and often uses PhotoShelter to deliver his images to clients.

“I’ll call up the Panos guys in London and say, ‘Hey, this is a story that needs to be told.’ And then they try to find a client that’s interested in picking it up.”

“50% of the time, my stories are shelved,” he says. “But you have to have that gut feeling that a story needs attention. For me it’s not about the money anymore – it’s about what the story could do for people.” So he ends up going on location to places like the Dadaab Refugee Camps primarily because he was interested in the story.

While Sanjit believes in the stand-alone power of photography, Sanjit always tries to collaborate with a writer who can add the written piece to his story. Such was the case with these images, which are part of a larger work entitled, “Drought In The Horn of Africa”. Sanjit worked with Emily Dugan of The Independent in the UK to put together an incredible story of their visit to the Dadaab Refugee Camp this past year. In the featured article, she wrote:

“Only brittle thorn bushes and graying Acacia trees grow. Emaciated figures – once proud herders of huge numbers of livestock – slump by the road trying to sell scraps of charcoal to passers by that never come. Their last resort in times of hunger used to be the berries on the trees, but these disappeared three months ago. Even the camels – unable to cope with the hunger and thirst – are dying now.”

The refugee camp opened in 1993 as a temporary relief measure for people affected by the imminent drought. It was built to hold 90,000 refugees; in July 2011, an estimated 465,000 people were living in the camps. About 1,000 new refugees are arriving every day, and by 2013 a projected half a million people will be living there and surviving solely on humanitarian aid.

Given that the drought has actually worsened since the camps opened, and the current civil war in Somalia, most refugees have no intention of going back to their homeland. They have hopes and aspirations of moving to a new place, but it feels like there is zero opportunity to do so.

“These are the sort of things that are happening in the so-called ‘civilized world,’” says Sanjit. “Still, most of us rarely think about these issues of survival that are still happening all around us today.”

During his visit to Dadaab, the thing that tore at Sanjit’s heart again and again were the refugees’ gaunt, empty stares. “There’s something profoundly different in lives of people in these extreme situations,” he explains. “I met this woman who traveled to the camps with her three and six-year-old granddaughters, and along the way the girls were raped. And you think, “What kind of desperate human being would rape a three and six-year-old?”

Then there’s the story of the woman who had walked for 17+ days before leaving her children behind because she was too weak and exhausted to carry them any further. Or the man who left his wife and children when he was offered a truck ride, promising that he would get a ration card and UN accreditation so that he could feed his family when they arrive. If they arrive.

These were the kinds of stories Sanjit heard on a daily basis during his visit, and he tried to capture the story-tellers’ feelings in his photos. In fact, Sanjit is often caught between two worlds whenever he’s photographing in a despairing community – on the one hand, he strives to spend time with people and build rapport so that he can gain true insight into their lives; but on the other hand, he maintains an emotional distance so that he can objectively document the situation.

Not every photographer strives to find such a balance with his subjects, especially in such extreme situations, but Sanjit thinks this is one of the most important steps to creating strong documentary photography.

“I spend a lot of time in the communities,” he says. “I break bread with them, if there is bread, and I’m aware of their cultural norms. They know that I’m a photographer but that I’m also there to spend time with them. People open their doors when you tell them that you’re there to listen to what they have to say and tell their story.”

It seems like these days Sanjit is constantly on the move to work on stories that he thinks need a voice. Among his other outstanding bodies of work are:

- A collection spanning almost three years of documenting the land-rights movement in India (“Farmers and Industry Battle Over Land”) and the continuing violence in northeast India (“India’s Hidden War”)

- Photos of Bokapahadi, India residents who live above coal mines collecting small chunks for $2 a day (“Hell Beneath Earth”)

- Surrogate mothers at a clinic in Gujarat, India, the most popular clinic for outsourcing pregnancies by western couples (“Rent-A-Womb”).

You can view Sanjit’s complete galleries on his website, sanjitdas.photoshelter.com. And for more information on his work for Panos Pictures, search for Sanjit Das on www.panos.co.uk/photographers.

What effect do Sanjit’s photos of the refugee camps in Dadaab have on you? You can make a difference by donating to CARE, one of the leading humanitarian aid organizations working in the camps. Click here for more information.