Share

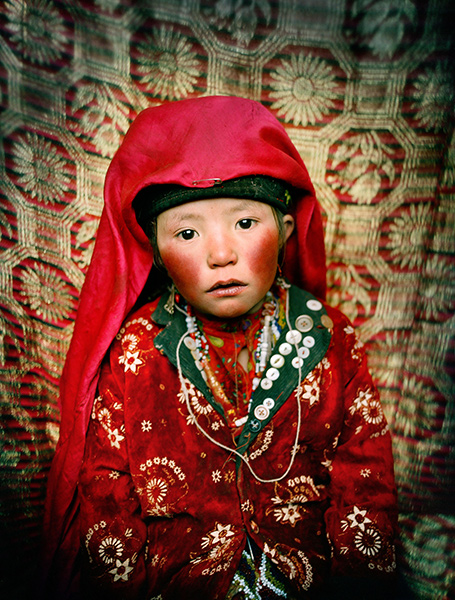

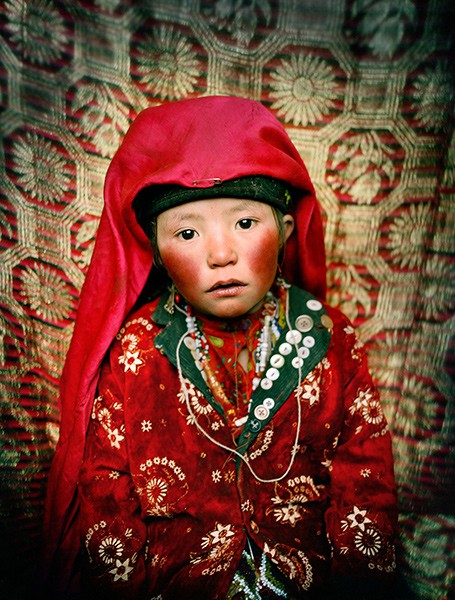

Climbing to the Roof of the World with Matthieu Paley

Each week we’ll feature one photographer from the PhotoShelter community, and share his or her story behind the shots that caught our eye. Photog...

Each week we’ll feature one photographer from the PhotoShelter community, and share his or her story behind the shots that caught our eye.

- Photographer: Matthieu Paley

- Specialty: Documentary

- Current Location: Turkey

- Clients: National Geographic, Newsweek, Time, Outside

- PhotoShelter Website: www.paleyphoto.com

The Story:

French photographer Matthieu Paley’s interest in the Pamir mountains of Afghanistan, home of a nomadic Kyrgyz and known as Bam-e Dunia, The Roof of the World, began back in 2000. According to Matthieu, creating his book Forgotten on the Roof of the World, which documents the people and lifestyle of Pamir “all happened very organically.” For him, there was never a master plan, just a curiosity and desire to find out more about the people and their culture.

Back in 2000 while working for an NGO in North Pakistan, Matthieu spotted a Kyrgyz caravan coming down a high mountain pass. At that time, Matthieu was unaware of the Kyrgyz culture and its people, but his curiosity sparked. From there, he began documenting the travelers on and off for several years.

One year, a caravan leader asked Matthieu to personally deliver a letter to his sister who lived in Turkey. The country had become home to a large community of Afghan Kyrgyz’s who had fled Afghanistan 25 years ago, following the Russian invasion.

Matthieu hand delivered the letter and it was the sister’s and other relatives written replies that motivated him and his wife, Mareile, to make the trek up to the Wakhan Corridor in Afghanistan to personally deliver the 13 letters. “We trekked for over 300 KM. It was incredible. We were just the 2 of us – no guide, no porters.” Matthieu and Mareile walked every day for 5 weeks, delivering the letters and putting family members in touch who hadn’t spoken in over 25 years.

After that trip, they were hooked. They knew they wanted to return, but next time during the winter, which there, lasts a solid eight months and is relentlessly cold.

Matthieu describes the process of having the Afghan Kyrgyz community open up to him and the idea of being photographed as “difficult and slow.” “The nomadic Kyrgyz can seem rough, like the bleak and lunar environment in which they live,” he explains.

Up there, it’s no easy-living. Pamir has the world’s highest infant mortality rate, and half the children die before reaching the age of 5. This, combined with the difficulty to access proper medical care, has led the nomadic Kyrgyz’s to turn to the use of opium as medication.

Early on, Matthieu learned one of the native languages, Wakhi. This direct interaction enabled Matthieu to connect and become intimate with the environment, “intimacy – with respect – is the key to good photographs, to telling a true story,” he claims. Matthieu always bring prints back from previous years to people. “It’s a small community – only about 1,200 people. I know most of them by now.”

Over the years the camera gear Matthieu traveled with to document the culture evolved, “I started with a Nikon F100 I think, one lens and a few rolls, then I used Xpan panoramic camera. Since 2011 I went three times with my Canon 5D and a bunch of fixed lens.”

Shooting digital meant schlepping solar panels, computers that could sustain high altitude, and back-up gear because of the extreme weather conditions. “It takes over 10 days of being on the road to see your first Kyrgyz in the Afghan Pamir. In winter, the only way up is by walking on a frozen river. It’s a true wilderness – you are really on your own, not like Everest base camp!”

It wasn’t until 2008, after Matthieu’s first winter expedition that he was inspired to make a book out of his work. “The community hadn’t been visited in winter by a foreigner since 1972. After that trip, I started to have a more complete view on that community. A book was the logical continuation.” Matthieu has recently published his body of work titled Forgotten on the Roof of the World in French and German and is currently in search of an English publisher.

What caught our eye:

Matthieu’s philosophy on the key to taking good photographs, intimacy combined with respect, shines through in his photos. Because of his curiosity, and ultimately his patience with the people of Pamir, Matthieu was able to capture a remote and little-known community in a beautiful and thoughtful way.