Share

The Ambiguity of Pressing the Shutter – Ethics in Photojournalism

The myth goes that Crazy Horse refused to be photographed, believing the image would steal his soul. In truth, the apocryphal tale has no historic...

The myth goes that Crazy Horse refused to be photographed, believing the image would steal his soul. In truth, the apocryphal tale has no historical evidence. But taking photos is intrusive, and most people would agree upon some near universal norms regarding photography (e.g. taking photos of children in public).

For photojournalists the ethics of photography are part and parcel of the job, and when to take a photo is a major component of those ethics. The issue boiled over again last week with the controversy surrounding disgraced photojournalist Souvid Datta whose shoddy plagiarism of a Mary Ellen Mark photo eclipsed a prior discussion of his photo of an alleged rape (“alleged” because we have no reason to believe the veracity of his captions or whether he staged a scene).

But questions regarding the rape photo remains central to the discussion of ethics. NPPA President Melissa Lyttle wrote, “According to the NPPA Code of Ethics, visual journalists are supposed to treat subjects with dignity and respect and to give special consideration and compassion to vulnerable subjects. As human beings, we have a moral obligation to do no harm.”

But the reality on the ground is often rife with ambiguity.

A Historical Perspective

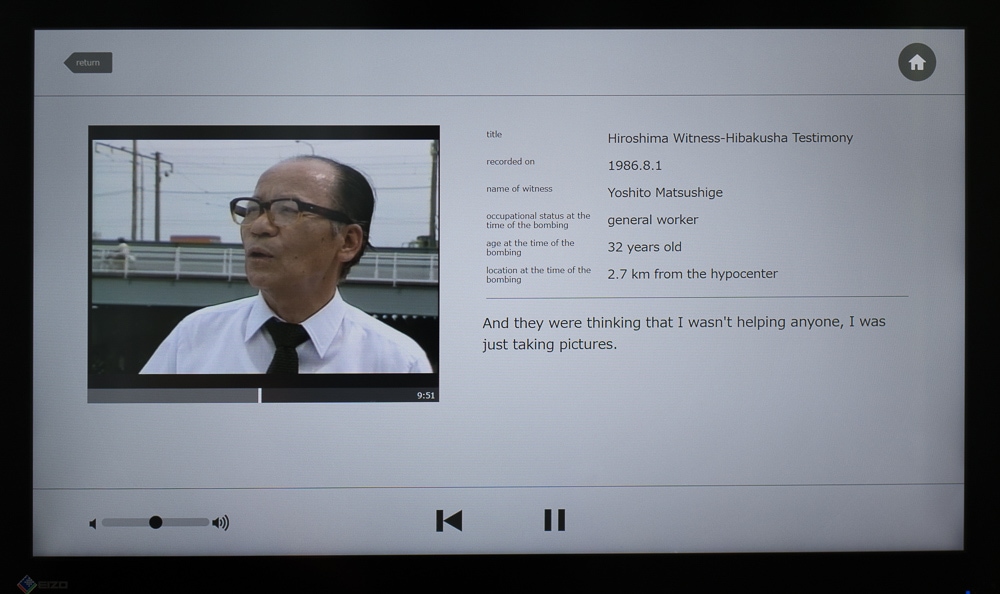

On August 6, 1945, the US detonated the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima which indiscriminately killed approximately 145,000 people within four months (half those deaths occurred on the day of the bombing). On the ground, photojournalist Yoshito Matsushige took the only known photos from the day.

In a 1986 interview for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Matsushige said, “I saw [all this destruction] and I thought about taking pictures – so I got my camera ready – but I just couldn’t do it. It was such a pitiful scene…But these children, any moment they would start dying. It was so hard to take pictures of them.” After twenty minutes, Matsushige mustered the courage to take two frames. “I felt like everyone’s gaze was fixed on me. And they were thinking that I wasn’t helping anyone, I was just taking pictures.”

Upon hearing that biographer/photographer Howard Bingham refused to take a photo of friend Muhammed Ali after a devastating loss to Joe Frazier, legendary photojournalist David Burnett thought to himself “that is exactly when you HAVE to take a picture,” but over time, he’s come to believe that “the line gets fuzzy much more quickly than you’d expect.”

The significance of his words shouldn’t be taken lightly. Burnett was famously standing on the same dirt road as Nick Ut, when Ut took one of the most famous photos of all time – a nude child screaming from napalm burns. The Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of Kim Phuc shifted public sentiment despite its graphic and gruesome content, which was notoriously censored from Facebook. But even Ut put his cameras down telling Vanity Fair, “I took almost a roll of Tri-x film of her then I saw her skin coming off and I stopped taking pictures. I didn’t want her to die. I wanted to help her. I put my cameras down on the road.”

Six months prior to the “Napalm Girl” photo, Burnett found himself unable to take a photo. While photographing the India-Pakistan war in December 1971, Burnett came across a Pakistani detainee in the town of Kulna whose fate was almost a certainty. “I walked across the room and took my camera up to photograph one of the prisoners. His expression melted into the most frightened face I had ever seen. He must have known exactly what his situation was, and no doubt was hoping this foreigner – me – would be his savior. There was really nothing I could do. But at the same time, as we looked at each other, I lost whatever journalistic energy had propelled me to that moment. I couldn’t take his picture.”

Photo by Ketevan Kardava

On March 22, 2016, a bomb ripped through the Brussels Airport. Reporter Ketevan Kardava photographed one of the victims – Nidhi Chaphekar, a Jet Airways flight attendant – in shock and with her clothing partially blown off her body. Critics pounced on the exploitative nature of the image. On the Huffington Post, Sandip Roy wrote, “Kardava is doing what is her job, to document a tragedy, possibly at risk to her own life. The media is doing what they think is their job – finding an image that drives home that tragedy. The only person who has no choice in this is the person in the photo splashed around the world.” Yet, the quick circulation of the image allowed Chaphekar’s family to know she was alive.

More recently, Syrian activist and photographer Abd Alkader Habak put down his camera to help victims of a bus convoy bombing. “The scene was horrible — especially seeing children wailing and dying in front of you,” Habak told CNN. “So I decided along with my colleagues that we’d put our cameras aside and start rescuing injured people.”

But at the same scene, photographer Muhammad Alrageb felt the compunction to take photos telling CNN, “I wanted to film everything to make sure there was accountability.”

The intricacies of sex, violence and the gaze of “others”

Tim Matsui has covered child sex trafficking in America for many years with his “The Long Night” project, and has grappled with many of the issues that confronted Datta. “Since I mostly do slow stories, my metric is to ask, am I being exploitive?” Collaboration is crucial for Matsui, “In gaining access, I’ve had to fight a stereotype about the media’s exploitive nature. The key, I feel, is to not exploit someone in a vulnerable situation. It’s about helping them tell their story, not taking it from them for a better portfolio or clip.”

Syracuse Associate Professor of Newspaper & Online Journalism Seth Gitner agrees that photos need to advance a story, “There are other times when your journalistic senses kick in and tell you – wait, this has nothing to do with the story and has no journalistic meaning, so don’t bother taking the photo – but of course when an editor who is on the sidelines hears about what you may have missed – they may think otherwise.”

Adjacent to the issue of when to take a photo, is who should be taking it? More than one female commentator has questioned whether men should be photographing sexual trafficking, abuse and rape stories of women in the first place. One veteran photojournalist who wished to remain anonymous told me, “Compare Datta’s work to Stephanie Sinclair’s Child Brides, Yunghi Kim’s Comfort Women, or Jodi Cobb’s Geishas. I think a woman would have done [the Datta] story [with] a different approach.”

An outsider’s point of view can potentially sensationalize rather than inform, and critics have bemoaned the imperialist gaze cast upon “exotic” cultures. In an interview with the Huffington Post, ESPN Senior Photo Editor Brent Lewis emphasized the importance of having black photographers photographing black stories. “We are often represented as being poor, as if being poor is a quality. When I was in Chillicothe, Ohio, lots of African American’s were middle class. It is nothing like Chicago. Every place is distinct. So I had to dive into the history of this place. Too many people are trying to tell our stories without understanding our stories, I feel it is like my duty to go out there and tell our story.”

Rapport and Respect

Many photojournalists cite the importance of building a relationship between photographer and subject. Words like “dignity” and “respect” often accompany descriptions of how photographers should approach their subjects.

Pete Kiehart has photographed extensively in the Ukraine and France and explains that “I also work best when my subjects understand why I’m photographing them and when they’ve consented to being photographed.” But Kiehart recognizes that breaking news doesn’t always afford him that luxury.

When confronted with an ethically challenging scene, there are no guides to consult, and no online forums to query. Gitner says, “the relationship between photographer and subject is exactly that – between photographer and subject – only the photographer can be the one to make the decision ‘in the moment’ whether to shoot or not.”

Empathy and the Photojournalist

Would more photos from Hiroshima help us understand the horrors of nuclear weapons? Should Burhan Ozbilici have put down his camera at the assassination of Andrey Karlov? Are we justifying photographing horrible events, or do the photos really help build an understanding of complex topics and stories. Burnett says, “I have always felt that pictures, especially good pictures need a bit of soul and humanity to accompany technical talent. I think it is in that humanity that photographers try and find the balance. There is never a clear line, it’s one you feel, and sometimes you’re right, and sometimes – well – you’re just a photographer.”

It’s tragic that Datta’s photo was the catalyst for the current round of ethics discussions. And it should raise alarms within the industry that it took two outsiders, Benjamin Chesterton and Shreya Bhat, to raise the their hands and force a moment of introspection. But let’s be clear, ethics isn’t just a photographer problem. It took an industry of contest organizers, judges, photo editors, grant organizations, and publishers to allow questionable content and an ethically-challenged photographer to surface.

For every “obvious” scenario, there are dozens of ethically ambiguous situations. Do you preserve history at the expense of dignity? We will only gain clarity with an on-going discussion – not a punctuated dialogue that waits for egregious activity and a backlash of moral outrage.