Share

Portraits from a Genocide

Photographs act as records, and records are what the Nazis and Khmer Rouge sought to create during their brutal genocides of the 20th century. Port...

Photographs act as records, and records are what the Nazis and Khmer Rouge sought to create during their brutal genocides of the 20th century. Portraits of thousands of men, women and children taken shortly before their deaths is a savage reminder of the photo as a weapon, but ironically also illustrates how the photos came back to haunt the perpetrators as evidence of their crimes against humanity.

While the nature of these photos is the same, the tales of the photographers behind these images could hardly be more different.

***

As the Soviets advanced through Poland in late 1944, SS Commander Heinrich Himmler ordered the dismantling of the gas chambers at Auschwitz and any other record of the mass extermination that killed estimated 1.1 million people. Among the records, photos of the men, women and children before their deaths taken by a team of photographers led by Wilhelm Brasse.

14-year old Czeslawa Kwaka. Born August 15, 1928. Arrived December 13, 1942. Died March 12, 1943. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Brasse trained as a portrait photographer in the southwestern city of Katowice. After the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, Brasse, the son of a German father and Polish mother, was given the chance to join the Nazis. He refused and tried to flee the country, but was detained near the Hungarian border. After being sent to Auschwitz in 1941 as a political prisoner, Brasse was summoned by the Political Department for what he thought would be a death sentence. Instead, SS Officer Berhard Walter questioned Brasse about his knowledge of photography. His expert technical knowledge and proficiency in German lead to his appointment as the head of photo department of the Erkennungsdienst (the identification unit) as a part of the Nazi’s meticulous record keeping obsession.

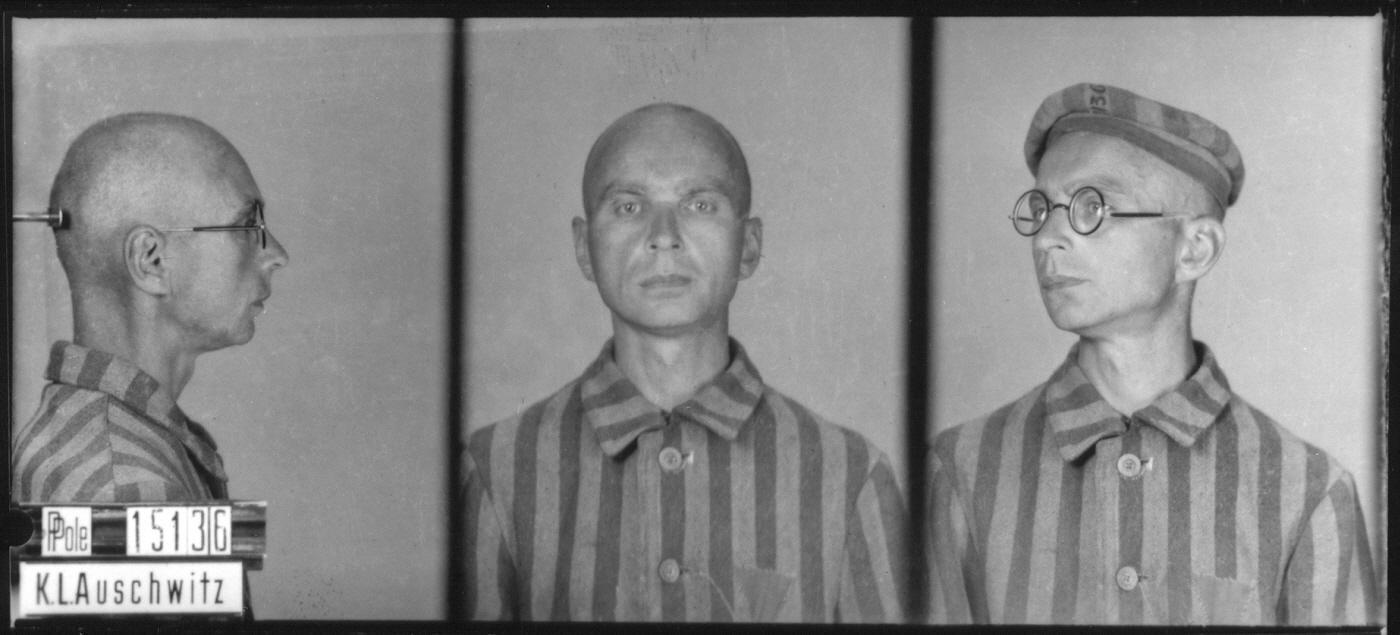

43-year old Waclaw Jacyna. Born August 7, 1897. Arrived April 22, 1941. Died June 13, 1942. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Anna Dobrowolska’s The Auschwitz Photographer contains interviews with members of the Erkennugsdienst who recounted the highly systematic work of photographing tens of thousands of prisoners.

From Janusz Karwacki:

“The camera had a Zeiss lens with 1.5 speed and focal lengths of 15 and 18 centimeters, set up for mug shots. We had also two large round reflectors. They used to 500W bulbs covered with special matte screens. Two main lights were used for mug shots. It was very harsh light.

“For portraits we used an additional smaller light to enhance the face. The background was a curtain stretched on a frame and set up in one spot. The portrait pictures used a gray backdrop, the mug shots a lighter colored one.”

From Jan Szemebek:

“Prisoners would come in one by one and sit on the chair. Actually, it was not a chair but a special cuboid with a crescent shaped support fixed to the back. The prisoners would lean their heads on that support to remain still. The crescent was mounted at about occiput level. It maintained a fixed distance between the face and the camera and thus made work more efficient.

“…There were three takes: the first one – prisoner wearing a cap and in three quarter view; the second one – with bare head and full face. For the third one the whole setup with the prisoner on the chair was turned ninety degrees and we shot his profile.”

Brasse estimates that he took 40,000 – 50,000 photos at Auschwitz. In addition to the mugshots of prisoners, Brasse also took portraits of various officers as well as documentary images of Josef Mengele’s victims.

When ordered to destroy all the images by Walter, Brasse and darkroom technician Bronislaw Jureczek ingeniously worked to save some negatives. In a 2005 Guardian interview, Jureczek said, “We put wet photographic paper and then photographs and negatives into a tile stove in such large numbers as to block the exhaust outlet. This ensured that when we set fire to the materials in the stove only the photographs and negatives near the stove door would be consumed, and that the fire would die out due to the lack of air.” They succeeded in saving over 39,000 images that have since been cataloged and digitized.

After the war, Brasse tried to return to a career in photography, but the spectre of his experiences made it impossible for him to continue. In 2005, Poland’s TVP1 released an acclaimed documentary entitled “The Portraitist” that chronicled Brasse’s life. Brasse passed away at the age of 94 in 2012, celebrated as a hero for risking his life to save thousands of images that remain the only visual evidence of those who were killed.

***

Fifty-four hundred miles away and thirty years later, Pol Pot reigned over Cambodia’s Killing Fields – a state-sponsored genocide to purge politicians, professionals and intellectuals, which resulted in the death of an estimated 25% of the population in a four year period of terror.

In 1976, the communist Khmer Rouge took over the Tuol Svay Pray high school in Phnom Penh. Innocuously renamed “S-21,” the military converted classrooms into prisons and torture chambers. An estimated 14,000 people passed through S-21’s doors and only seven survived.

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

As a part of the intake procedure, a 16-year old Chinese-trained photographer, Nhem En, was tasked with taking portraits not too dissimilar from Brasse. In a 1997 interview with Doug Niven, Ehn explained:

“We had 35mm, 6x6cm and 16mm cameras, which were taken from Phnom Penh photo shops. The 6x6cm film — very popular at the time — was the easiest to find, and simple to process. We also found Japanese-manufactured chemicals: borax, kenon, bolsovik, and carbonate from the shops. I learned how to mix the chemicals from the book I was given in China, to which I added translated notes/instructions in Khmer.

“I had a lot of cameras, but my favorite was [a] Yashica, made in Japan. I learned how to measure the light while I was in China, and to make the correct exposure.”

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

In a 2014 interview with Michael Klinkhamer, En recounted:

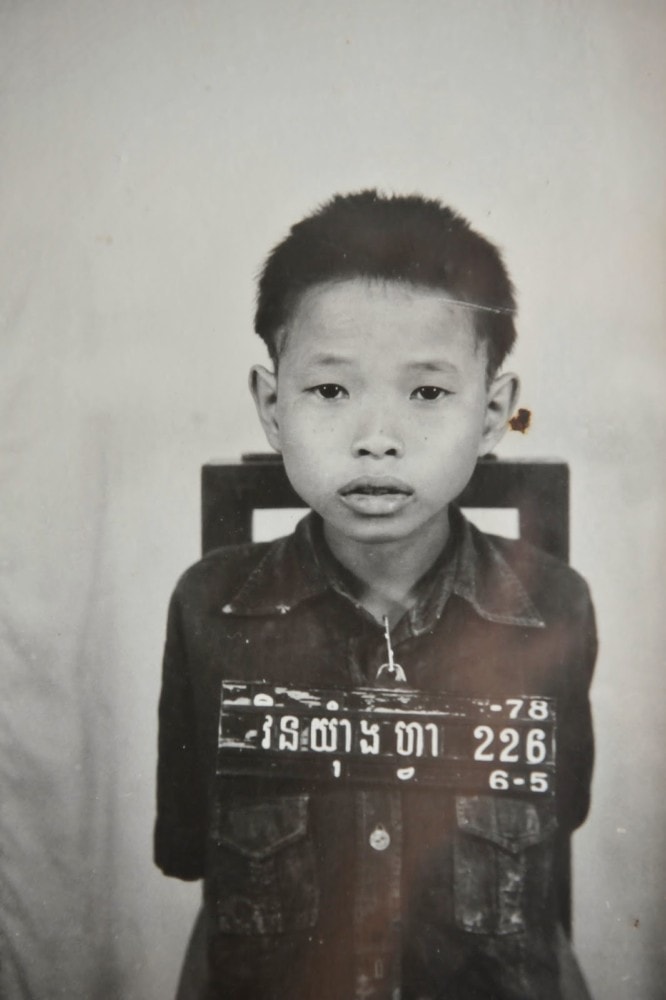

“Each prisoner was given a number and was registered on a list. I told them to look straight into the camera. No head turning or looking away, or the picture would not be suitable. The prisoners often had children with them. I also took pictures of their children.

“I used several cameras – the Rolleicord and Yashica …. and also a Canon. I used flash, and worked with a permanent set-up.”

Technically speaking, En’s photos benefit from faster film and better gear. The style and feel of some of these portraits is hauntingly contemporary, but the knowledge of what became of the subjects significantly alters aesthetic considerations. They are death photos taken by a man with little remorse over his role at S-21, often expressing pride in what he did.

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

When queried by Klinkhamer about what he would say if he would say to the victims, he tersely responded, “I have nothing to say to them. In those days we had to obey our leaders and follow their orders.”

“I had my job, and I had to take care of my job,” he told the New York Times in 2007. “I had to clean, develop and dry the pictures on my own and take them to Duch by my own hand. I couldn’t make a mistake. If one of the pictures was lost I would be killed.”

***

However seductive it might be to decipher differences in the expressions of the deceased based on the photographer, the exercise is specious. The content of the photos is the same – systematically created images of people moments from pain and death – but the context around the creation of the images brings nuance to our understanding of photography and its role in our humanity. We are responsible for how and when we push the shutter. We are responsible for how we choose to publish. And we are responsible for providing context that brings meaning and dignity to our subjects. Both photographers have photos, but only one has his morality.