Share

Now That You’re Outraged, Register Your Damn Copyright

Photographer Max Dubler struck a nerve with an article documenting the theft of one of his downhill skateboarding images. After finding a skateboar...

Photographer Max Dubler struck a nerve with an article documenting the theft of one of his downhill skateboarding images. After finding a skateboard brand using one of his photos without authorization, he did as he always does – he contacted the offending party and requested a payment of $25 for social media usage.

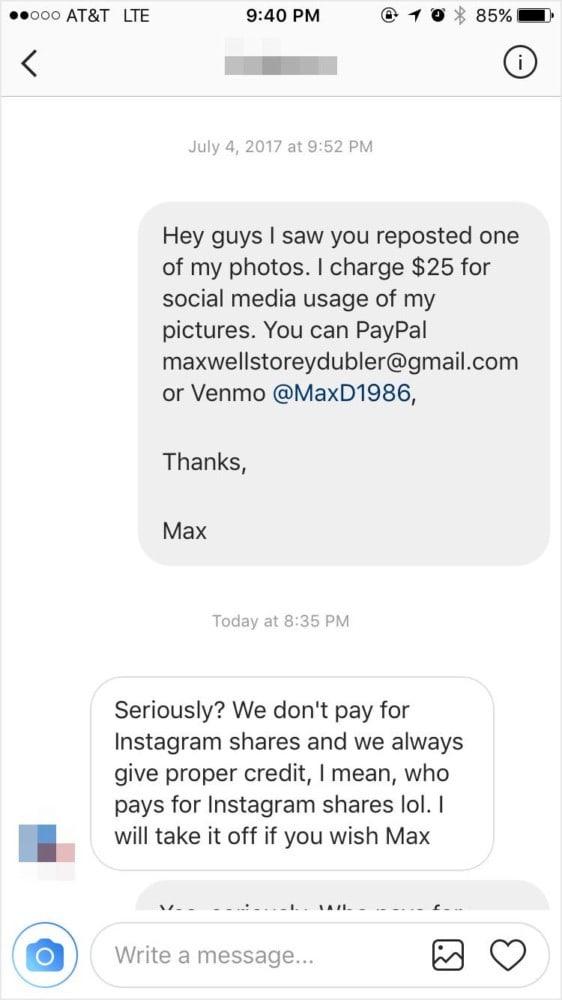

Dubler’s straightforward, non-confrontational strategy has worked in the past, but not this time. The offending brand responded:

“Seriously? We don’t pay for Instagram shares and we always give proper credit, I mean, who pays for Instagram shares lol. I will take it off if you wish Max”

Dubler spent considerable effort constructing a line-by-line response, which drummed up photographer outrage. But the central problem remains. Dubler writes, “They still haven’t paid me. I doubt they ever will, but in the 48 hours since those posts went up, half a dozen companies have contacted me to pay for for skate photos I didn’t even know they’d used. I’m calling it a win.”

Dubler scored more than a moral victory given that the piece led to newfound revenue. But his frustration and the outrage that it provoked did nothing for the long term benefit of photographers because of one simple thing: he didn’t register his copyright.

When I emailed Dubler about copyright registration, he responded “I didn’t, mostly because copyright exists from the moment of creation and I rarely ever have disputes about it.”

In the US, a photographer does own the copyright the moment he/she presses the shutter. But damages for willful infringement are generally capped at the market value. Presumably $25 in Dubler’s case since that is the precedent he set. But when you register your image with the US Copyright Office, you can be awarded up to $150,000 per image for a willful infringement plus legal costs.

And according to The Copyright Zone authors Jack Reznicki and lawyer Edward Greenberg, you can still register a photo even after it’s been infringed. “And we advise to register it even then. You just lose some rights that you would have if registered before the infringement, which is the right to statutory damages and collecting your lawyer fees. In some cases that may be a deal breaker for some cases, but then there is the Alan Paul Leonard case where the photographer was awarded $1.6 million plus $400,000 in interest for a registration done after the fact.”

The public doesn’t understand copyright

As Dubler incident illustrates, most people have a poor understanding of copyright – an issue that is exacerbated by social media sharing. Most of the major social media platforms have an embedding features that usually falls under a “share” link or icon. Embedding is generally seen as a mechanism that doesn’t run afoul of copyright laws because the Terms of Use usually require the uploader to consent to embedding.

But taking posted content and republishing it in one’s own account is equivalent to making a copy, and that is illegal. That Dubler’s image appeared in Instagram doesn’t mean another account can “share” it by uploading it to their account.

The threat of fines are a defense against infringement

Insect photographer Alex Wild noted in Ars Technica, “Most copyright holders are individuals; most infringers are businesses. Things are broken.” Content creators don’t wield the power of a corporation, but copyright gives them some significant protections.

Reznicki and Greenberg said, “One of the facts about suing and collecting through settlement or trial a large amount, is that it greatly discourages future infringements.” Suing is, for better or worse, a check-and-balance on corporate exploitation.

Whether $25 is the “right” amount somewhat misses the point. The market will bear what it will bear, and $25 may very well be the value of a license for use on an Instagram account with a limited following. The larger issue is that a lack of enforcement with punitive damages means that brands will continue to deprive photographers of a way to make a living.

Photo by Allen Murabayashi

Still Reznicki and Greenberg caution against sending an invoice out of the blue, in part because indicating an amount in an invoice reduces your leverage in court. If you’re trying to solve an infringement amicably and without a lawyer, they suggest, “send an email (not invoice) which states that ‘Rather than consult with my attorney I will accept actual receipt of the sum of $X not later than [date]. If I do not physically receive that money by that date my offer to resolve this matter shall be deemed withdrawn, null and void. I will then turn this over to my lawyer.’”

Register your damn images

Photographers can be their worst enemies. The US Copyright Office provides an online mechanism that is simple and relatively inexpensive. Yet, most photographers don’t regularly register their copyright despite knowing that infringements occur all the time.

At the urging of some readers, Dubler has set up a Patreon account. But soliciting small donations from strangers is an unsustainable way to make a living.

“I’m thinking of registering some of my more frequently stolen photos, though.”

The information contained within this article should not be construed as legal advice. Always consult a lawyer.