Share

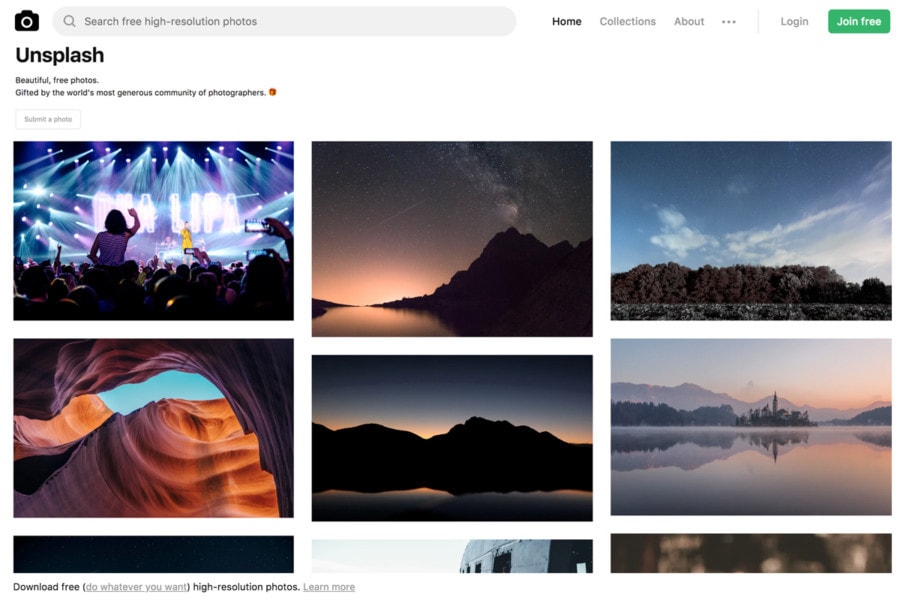

Unsplash is (Still) Bad for Photography

According to their mythology, the creative services company Crew only had a few months of operating cash left. They needed to do something to keep ...

According to their mythology, the creative services company Crew only had a few months of operating cash left. They needed to do something to keep the lights on, and with the leftover images from a commissioned photo shoot, they put up 10 images for anyone to use for free. That website, Unsplash, became a massive repository of free stock images, and more importantly, it became the top referral mechanism for new business for Crew. A side bet turned into the most potent marketing mechanism for the company and literally kept them in business.

Unsurprisingly, building a platform of free photos rubbed many professional photographers the wrong way. So much so, that co-founder Mikael Cho recently penned a defense of the business. I don’t believe that Cho has any malicious intent to harm the photographic industry, but I think the unplanned success of Unsplash has helped him to justify some untenable positions. Let me challenge some of Cho’s claims.

“New platforms don’t kill industries. They change the distribution.”

There have been inherent benefits to the direct-to-consumer platforms that have sprung from the Internet and app landscape. But platforms disproportionately benefit the platform owner, usually at the expense of content creators.

In a previous life, I was a founding employee of hotjobs.com. We built a job board that moved jobs classifieds online. This shifted the revenue from newspapers to an internet company. It was devastating to the newspaper industry, but it also brought a host of new efficiencies. Jobs were now searchable. Resumes could be stored online. Applications could be made electronically.

Unsplash isn’t so much a new platform. It’s the same platform that has existed at Getty Images, Shutterstock and the like. Except you don’t have to pay for anything. The distribution channel didn’t change – they simply removed a barrier from the distribution, namely price.

“When two-time #1 New York Times best-selling author Tim Ferriss was blocked from distributing his book in Barnes & Noble, he uploaded excerpts from his book for free on BitTorrent to get distribution.”

Besides Ferris, Cho also mentions writer Leo Baubata and Chance the Rapper. In other words, his justification for “free” rests with outliers. In any system, outliers are, by definition, not representative of the average. Cho could build a compelling argument if he had statistics showing that the majority of photographers had increases in business after displaying images on Unsplash, but of course, this isn’t true. Nor does Unsplash have an incentive to track this information in the first place.

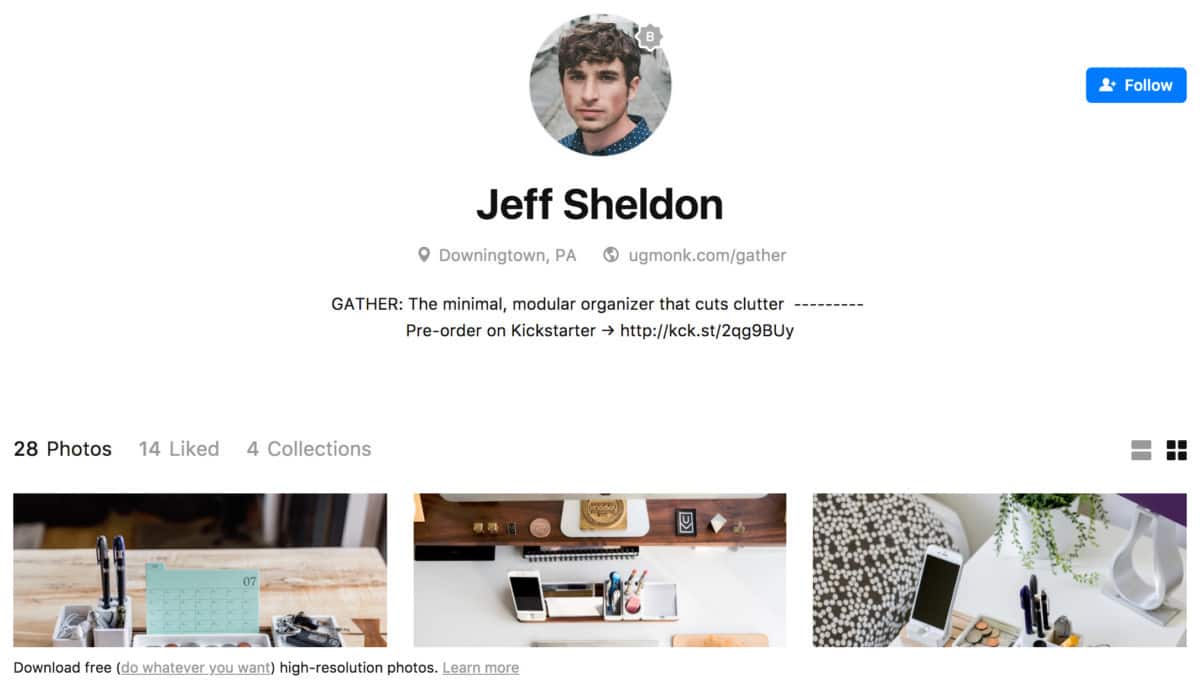

One of Cho’s other examples is designer Jeff Sheldon. He’s not a photographer by profession. He sells merchandise, and his oft-visited Unsplash profile features images of the products he’s selling. It’s a brilliant marketing move, but it’s also one that shows what the photography industry is up against. Photography isn’t his business, but it helps support his business – and he’s skilled enough to do it himself, which perhaps helps justify “free” in his mind.

“Before the internet, holding on to copyright for photos was more beneficial because the value in licensing a photo was high. The issue today is a licensed photo is losing its value…At the same time, the cost to produce a photo is going down…While professional photography gear is still expensive, mobile cameras are improving at a rate that will eventually put a professional-level camera in everyone’s pocket.”

If photos had no value, then others wouldn’t seek to use them. The cost of simply pushing the shutter button has gone down. But the cost of being in the right place and the right time and possessing the skill to take a great shot is the same as it ever has been. Yes, the value of a photo has decreased with digital photography, but the value of a good photo is not zero.

Unsplash likes to point out everyone from bloggers to Apple have used their images. It’s tragically ironic for Cho to boast about this. A photographer who spends $800 on an iPhone directly helps Apple’s bottom line, but she receives no such benefit when her image is used from Unsplash by Apple.

“Before the internet, holding on to copyright for photos was more beneficial because the value in licensing a photo was high.”

In the internet-enabled world, we’ve come to expect a frictionless system for commerce. To some, copyright is seen as a clunky, outmoded mechanism. But protecting a creator’s rights through copyright isn’t the problem. In many cases, it’s that licensing mechanisms haven’t been developed to work at internet speed. I know, I’ve been trying to receive a license to use a song from a copyright holder for 9 months.

For every high profile copyright infringement case you hear about, there are probably a dozen cases that are settled out of court. The US Copyright Code allows for statutory damages of $150,000 per image per willful infringement. The threat of penalty prevents business from stealing this form of intellectual property.

“Giving up your copyright to a photo seems extreme but it’s this extreme level of giving that produces the unprecedented level of connection.”

Photographers submitting their images agree to allow Unsplash to extend a royalty-free, irrevocable, perpetual license to anyone for any use. The notion that giving away something for free creates an “unprecedented” level of connection is an incredibly dubious claim. A housekeeper at the last hotel I stayed at gave me a few extra cookies for free when I passed her in the hallway. It didn’t create an unprecedented connection. I didn’t even get her name.

“If someone needs a photo for a presentation that will only be seen by a few co-workers, they don’t have a budget for photography. If they can’t use a free photo for that, they are not hiring someone. And there is no relationship created. But by finding a photo on Unsplash, a relationship begins. When they need to hire a photographer for a shoot, they’re more likely to go back to the place that fulfills that need.”

This is such a load of crap that I don’t know where to begin. If the presentation is only going to be seen by a few people, then why does it need photography? To make it more interesting? To create visual interest? If so, then we’ve just proven the value of photography. Should an internal presentation require a $1000 photo budget? Of course not, but paid licensing mechanisms already exist for small usage at a modest price.

Further, Unsplash’s license doesn’t even require crediting the photographer. The platform can’t even stand behind the thin marketing exposure argument

Some other nitty gritty details to consider:

- Their terms include an indemnity clause for photographers. If Unsplash is sued for your photo (e.g. trademark infringement), you’re liable.

- You agree to arbitration. Arbitration isn’t inherently bad, but if you’re sued by a big corporation in the court system, your only recourse with Unsplash is through arbitration.

- Model released image have no guarantee. This is actually true with any platform. But established companies like Getty Images – whose revenue is built around image licensing – have a financial incentive to double check this detail. Caveat emptor.

Cho concludes with:

“Every industry evolves. Things will change. We can’t be resistant to change no matter how much today’s world benefits us. We face the same fact that every artist and business must face: what we offer today will eventually be obsolete. We can choose to be upset with this fact or understand it is inevitable and continue to adapt.”

This is so generic to the point of being worthless. Who can dispute that things will change and you can either adapt or die? Another aphorism to throw on a t-shirt. But it lacks any nuance of the real world.

Free isn’t the answer. It’s not sustainable. If you value any craft, then you need to pay for it. There are costs associated with any craft, and even a hobbyist needs to figure out how to justify a series of on-going expenses.

Unsplash created a platform. They didn’t force anyone to use it. Creatives who use Unsplash bear an enormous responsibility for assuming that the sharing economy will somehow magically work for photography when it hasn’t worked for any other creative field.

But Unsplash does bear responsibility for arguing a position filled with unsubstantiated claims and conflations. As a fellow entrepreneur, I know how hard it is to build and stay in business. I don’t begrudge Cho’s success at all. But Cho’s support of the industry – especially insofar as professional photographers are concerned – is a mirage. Photography is a means to an end for his company. He has no incentive to declare that photography has any monetary value. The very success of his company depends on photography being worthless.

And that’s why Unsplash is bad for photography.