Share

Using Photos to Fight Hate: For Better or Worse

On August 10, 2017, the popular podcast Radiolab published an episode entitled “Truth Trolls,” which recounted the story of actor Shia Lebeouf�...

On August 10, 2017, the popular podcast Radiolab published an episode entitled “Truth Trolls,” which recounted the story of actor Shia Lebeouf’s “He Will Not Divide Us” performance art protest against Donald Trump’s ascendency to President of the United States. After a number of heated incidents in New York and Albuquerque, Lebeouf moved the project to an undisclosed location, deciding to train a webcam on a flag that read “He Will Not Divide Us.”

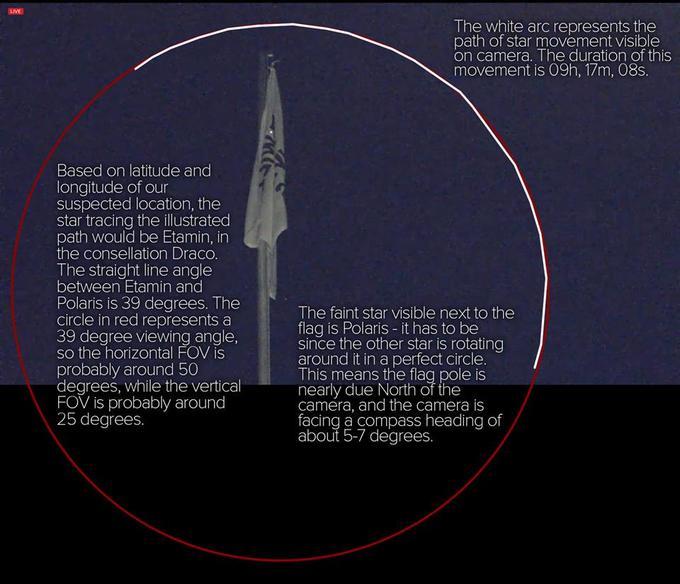

Users on the notorious website 4chan, which has been linked to fringe movements like alt-right, Anonymous, and internet trolling used a series of visual clues – including a sighting of LeBeouf on Instagram which dramatically narrowed the search radius, stars, and airplane flight paths – to track down the location of the flag in Tennessee, and replace it with a “Make America Great Again” hat and Pepe the Frog t-shirt. It was a doggedly persistent example of forensic sleuthing through images.

Then on August 13, Radiolab removed the episode, saying:

EDITORIAL UPDATE: Radiolab has decided to take down this episode. Some listeners called us out saying that in telling the capture the flag story in the way that we did, we essentially condoned some pretty despicable ideology and behavior. To all the listeners who felt that way, and to everyone else, please know that we hear you and that we take these criticisms to heart. I feel awful that the things we said could be interpreted that way. That’s on us. It was certainly not our intention, and we apologize.

And thus we confront one of the contemporary conundrums of images and culture. More than any time in the history of photography, images and metadata provide incredibly powerful ways to increase transparency and uncover “truth.” But the potential for malicious or misuse is high. And ironically, publicizing these incidents often brings attention to fringe ideologies.

The “Unite the Right” protest in Charlottesville this past weekend provides a tragic microcosm of this phenomenon.

Case 1: An Attention to Detail Leads to an Interview

The Columbia Journalism Review recounted how Toledo Blade copy editor Tommy Gallagher’s scrutinization of imagery led to the realization that the car involved in death of 32-year old Heather Heyer was from Ohio. The Blade was then able to identify the driver, James Alex Fields Jr., as well as track down his mother Samantha Bloom for an interview, at which point she was unaware of the events that thad transpired.

Case 2: A Hat That Did Not Belong and the Burn that Followed

The Huffington Post reported on an image circulating on Twitter of a white supremacist gesturing with the KKK salute wearing an 82nd Airborne Division hate. The 82nd Airborne Division tweeted in response, saying that anyone could buy the hat (insinuating that the man hadn’t served), and that the man didn’t reflect the unit’s culture and values.

Would *LOVE* to know the name of Mr. 82nd Airborne Division here rendering Hitler’s Nazi salute. The 82nd jumped into Normandy on D-Day. pic.twitter.com/oObJNgXzEI

— Brandon Friedman (@BFriedmanDC) August 13, 2017

U really think that guy is an active member of the 82nd just because he has that hat? My mom has that same hat. She’s 78 & has never served

— All American Division (@82ndABNDiv) August 14, 2017

But besides the “burn” against an alleged impostor for ironic use of hat, nothing of value was gained in the fight against hate.

Case 3: Crowdsourcing Identities Through Photos

The Twitter account @YesYoureRacist put out a call to identify marchers from “Unite the Right” march in Charlottesville. The identification of a number of participants resulted in their firing from their jobs, but a few misidentifications were also made – both incorrectly identifying a person who wasn’t there, as well as pointing to a person with a passing resemblance to a participant).

If you recognize any of the Nazis marching in #Charlottesville, send me their names/profiles and I’ll make them famous #GoodNightAltRight pic.twitter.com/2tA9xliFVU

— Yes, You’re Racist (@YesYoureRacist) August 12, 2017

University of Arkansas assistant engineering professor Kyle Quinn was misidentified as a marcher because of a t-shirt and facial hair. Quinn told The New York Times:

“You have celebrities and hundreds of people doing no research online, not checking facts,” he said. “I’ve dedicated my life to helping all people, trying to improve health care and train the next generation of scientists, and this is potentially throwing a wrench in that.”

@QuinnLab_UofA How do you find time to conduct research when you are so busy taking part in neo-nazi marches ? #nazimarch pic.twitter.com/3yciCi5DvH

— Next Level Apps (@NextLvlApps) August 12, 2017

The misidentification led to his doxing with internet users posting incendiary messages accompanied not only his place of employment, but his home address as well.

The fear of a police state armed with facial recognition databases is now augmented by activist citizens on both sides of the political spectrum, whose actions have very little personal consequence but can be devastating to their targets. The photo as weapon continues to evolve in ways that will continue to challenge our ethics and push the norms acceptability in society. Photos have never been literal markers of veracity and truth, and the chaos of misinformation unfortunately makes them increasingly dubious.