Share

How Photojournalism and Tech Intersect in “Texting Syria”

Our fascination with the relationship between photography and technology is no secret—in fact, it’s the subject of our latest podcast. We belie...

Our fascination with the relationship between photography and technology is no secret—in fact, it’s the subject of our latest podcast. We believe that understanding the impact of technology on society at large and our daily interactions with visual media is essential to understanding the future of photography.

Award-winning photojournalist Liam Maloney shares this belief, and his efforts to reconcile advances in communication technology with visual media are at the forefront of his recent project. Entitled Texting Syria, this work is a result of the two years Liam spent in Lebanon documenting the lives of Syrian refugees. Composed of an interactive collection of photographs and text messages, this project culminated in an installation examining the role of technology on the Syrian refugee experience.

Liam recently visited our NYC headquarters to showcase and discuss his project and its installation—co-authored with Daniel Arcé, one of our own developers—and explained that he was feeling like his work in photojournalism was getting repetitive. He was regularly shooting for newspapers and magazines covering the Syrian refugee crisis but felt that the connection between the subject matter and the audience was stagnating and losing its impact.

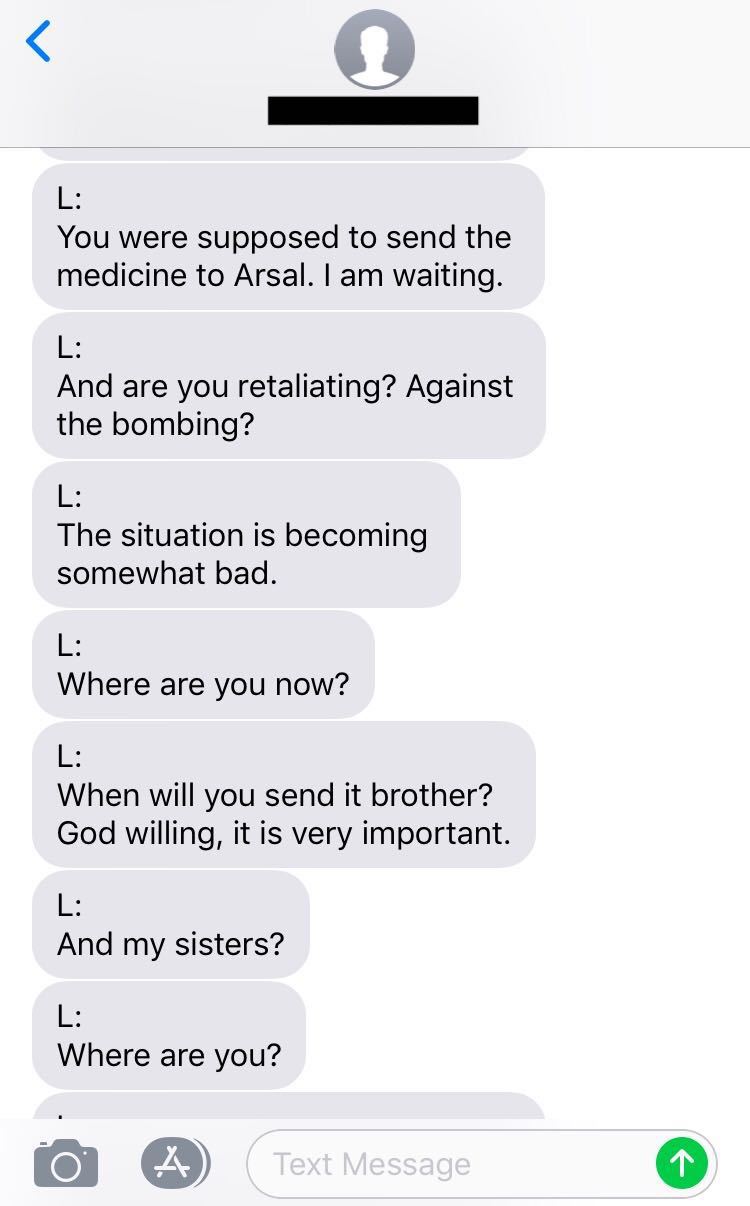

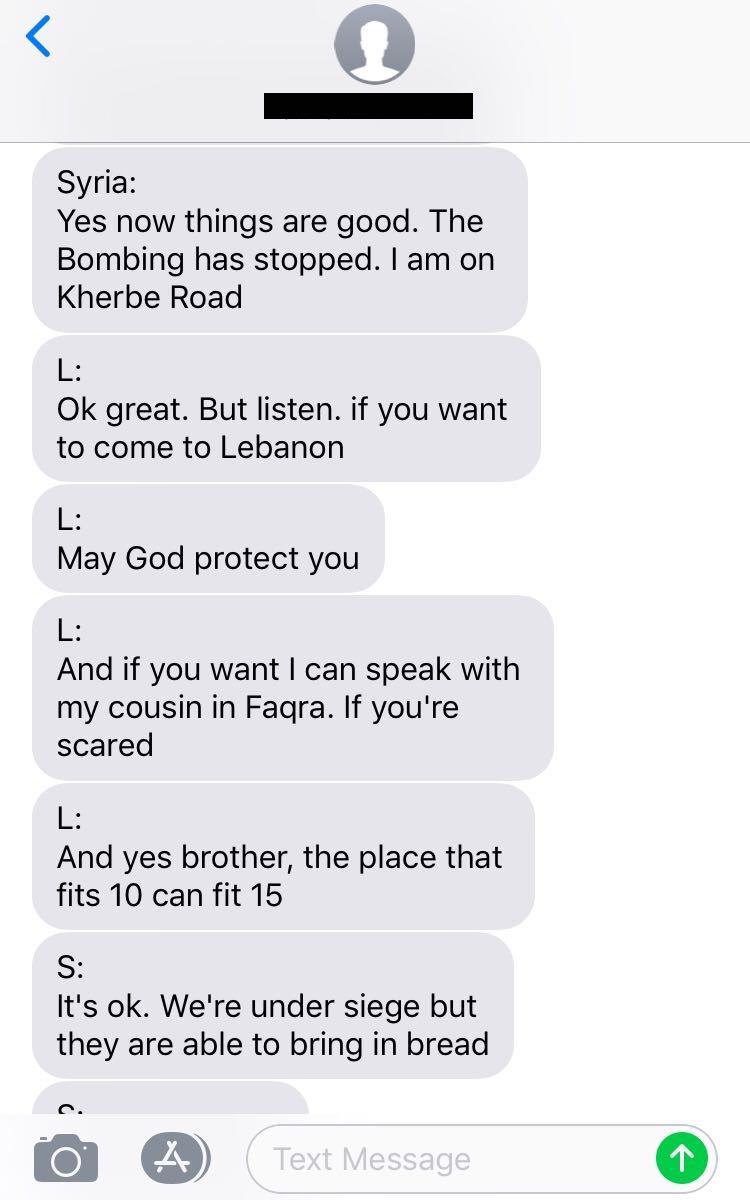

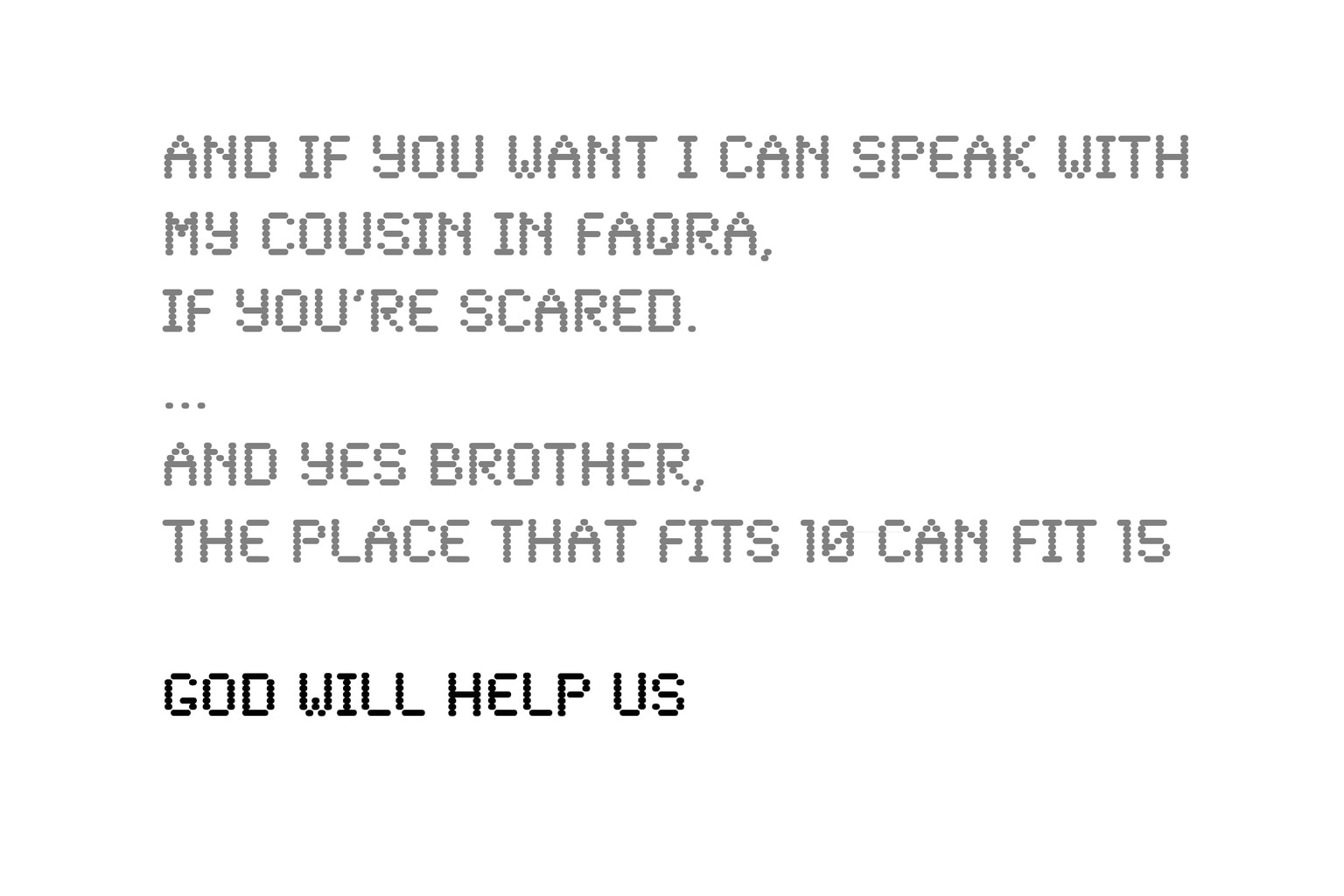

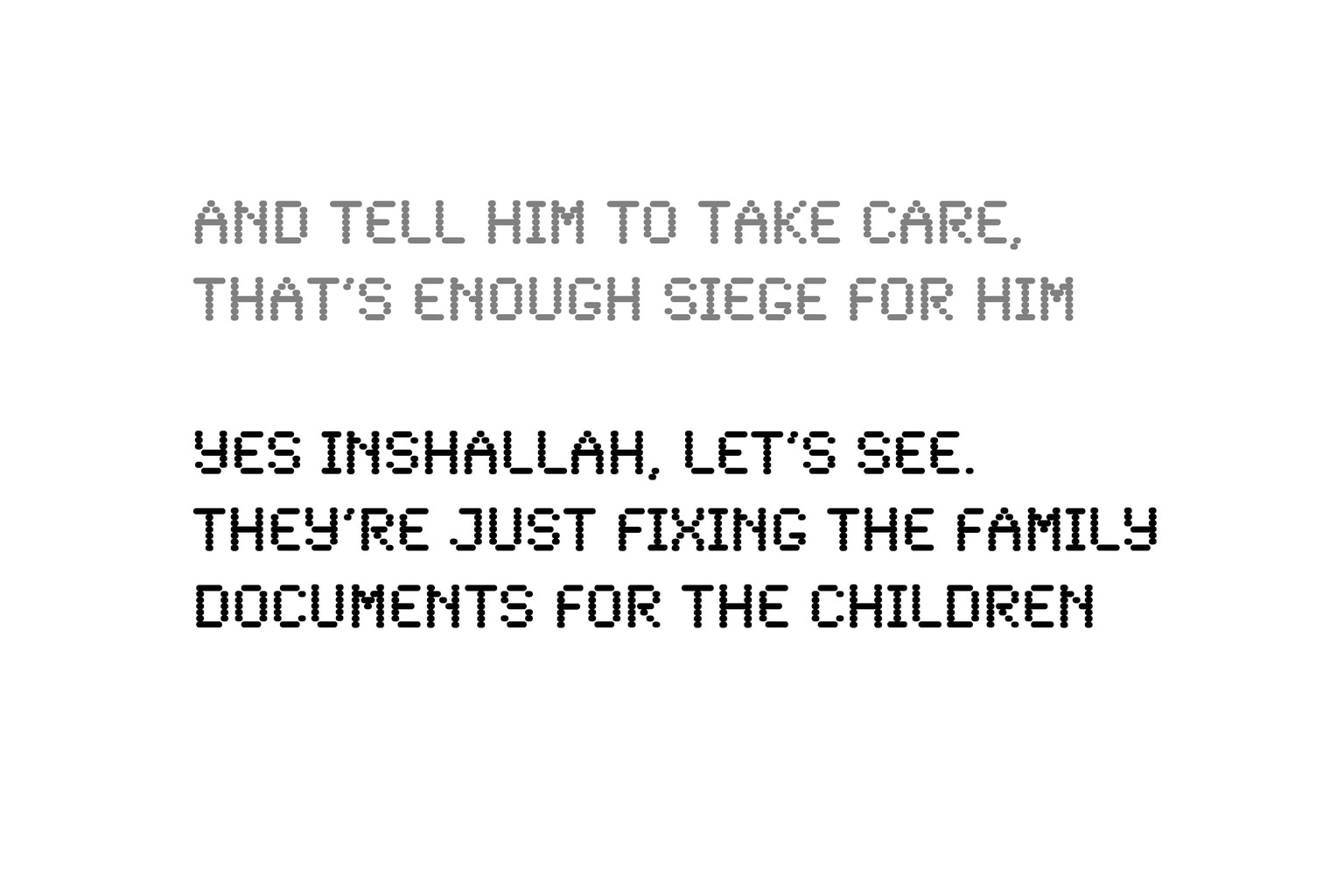

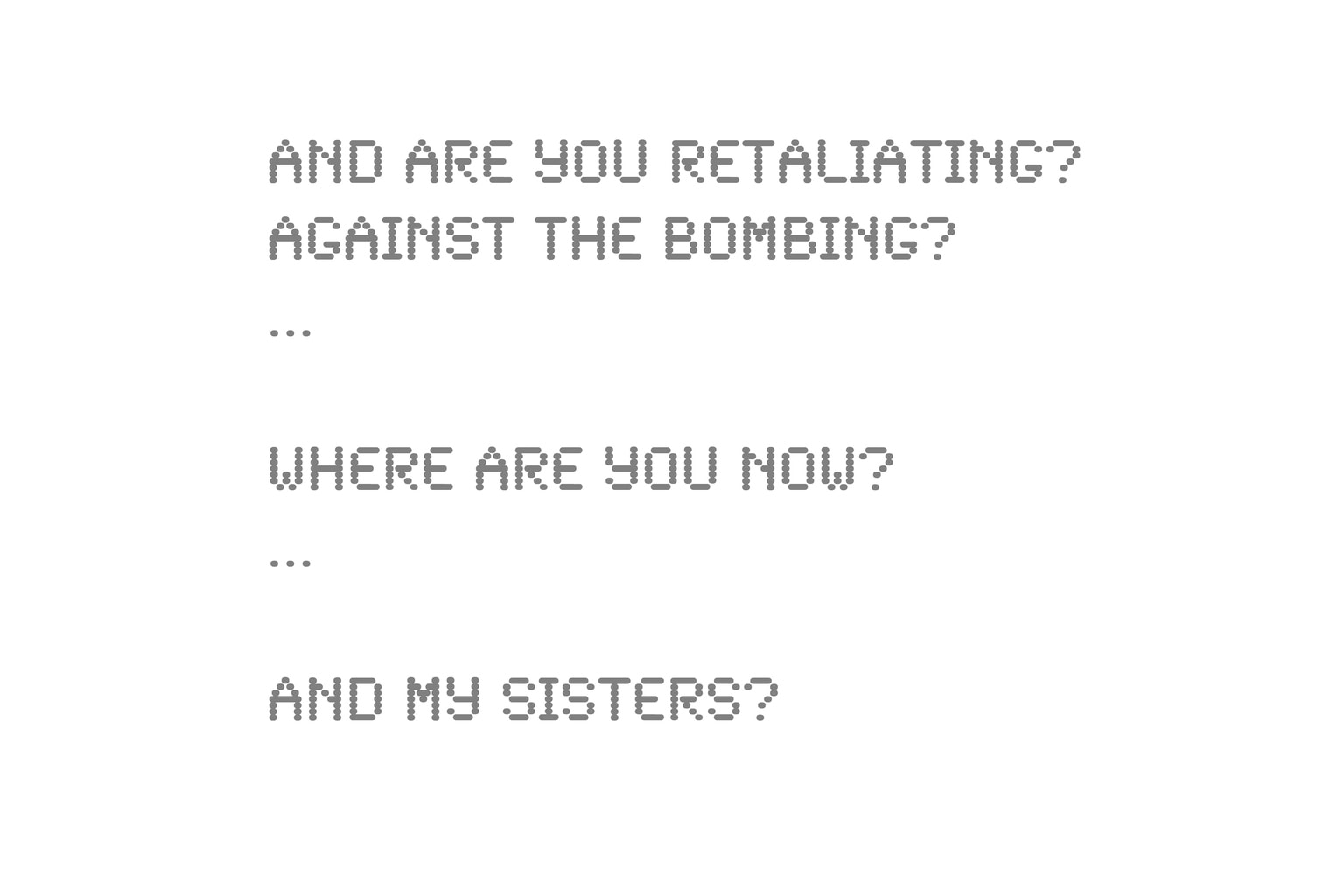

After watching refugees text their friends and family, many of whom were still under siege back home, Liam decided to explore the hidden narratives within the text conversations themselves. He spent time with sixteen families living in a camp inside an abandoned slaughterhouse in Akkar and asked if he could photograph their messages alongside his portraits of them sending their nightly correspondence. With the help of a translator and the trust of a community leader—a former teacher who introduced Liam to people living in the camp—the work took on a life of its own.

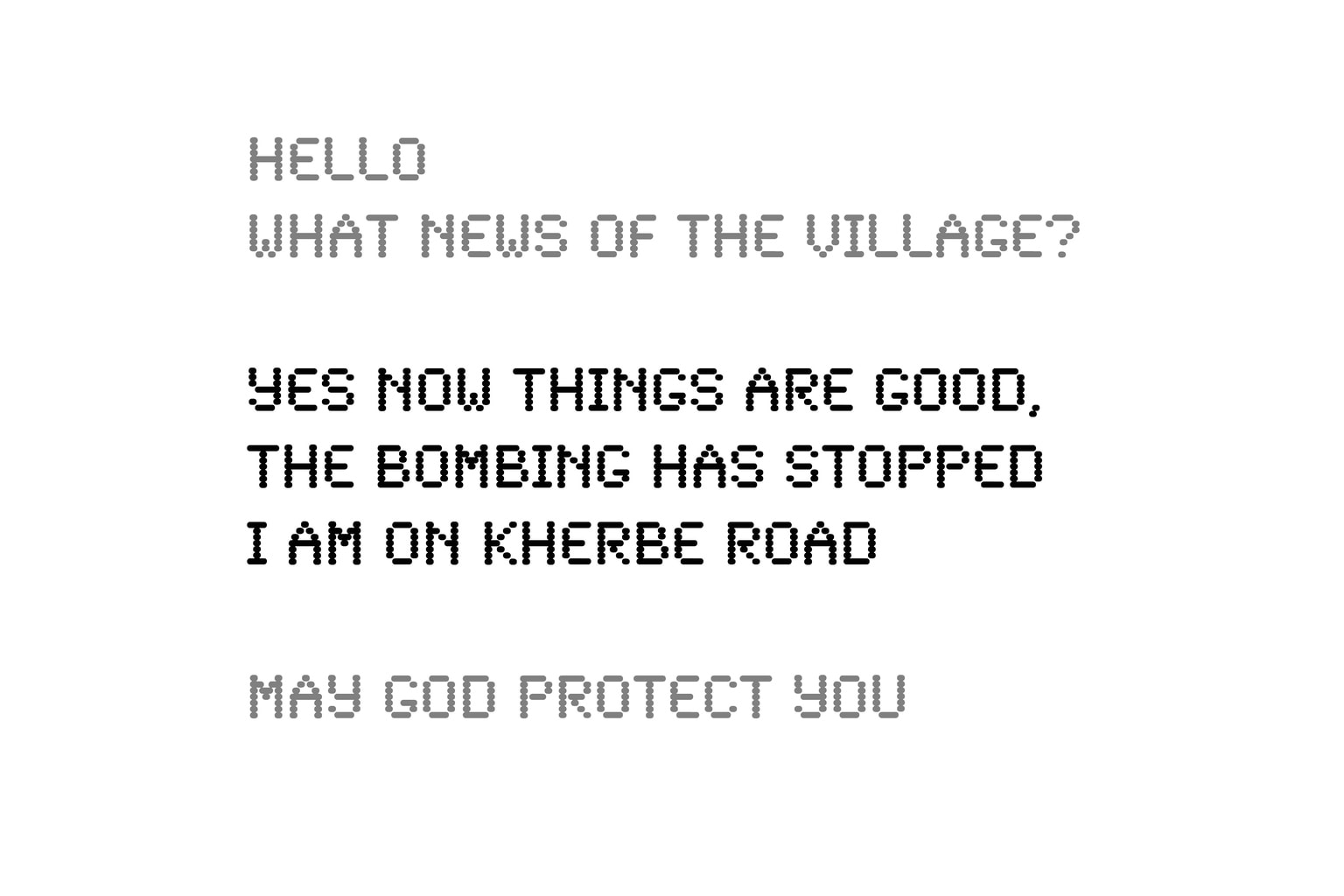

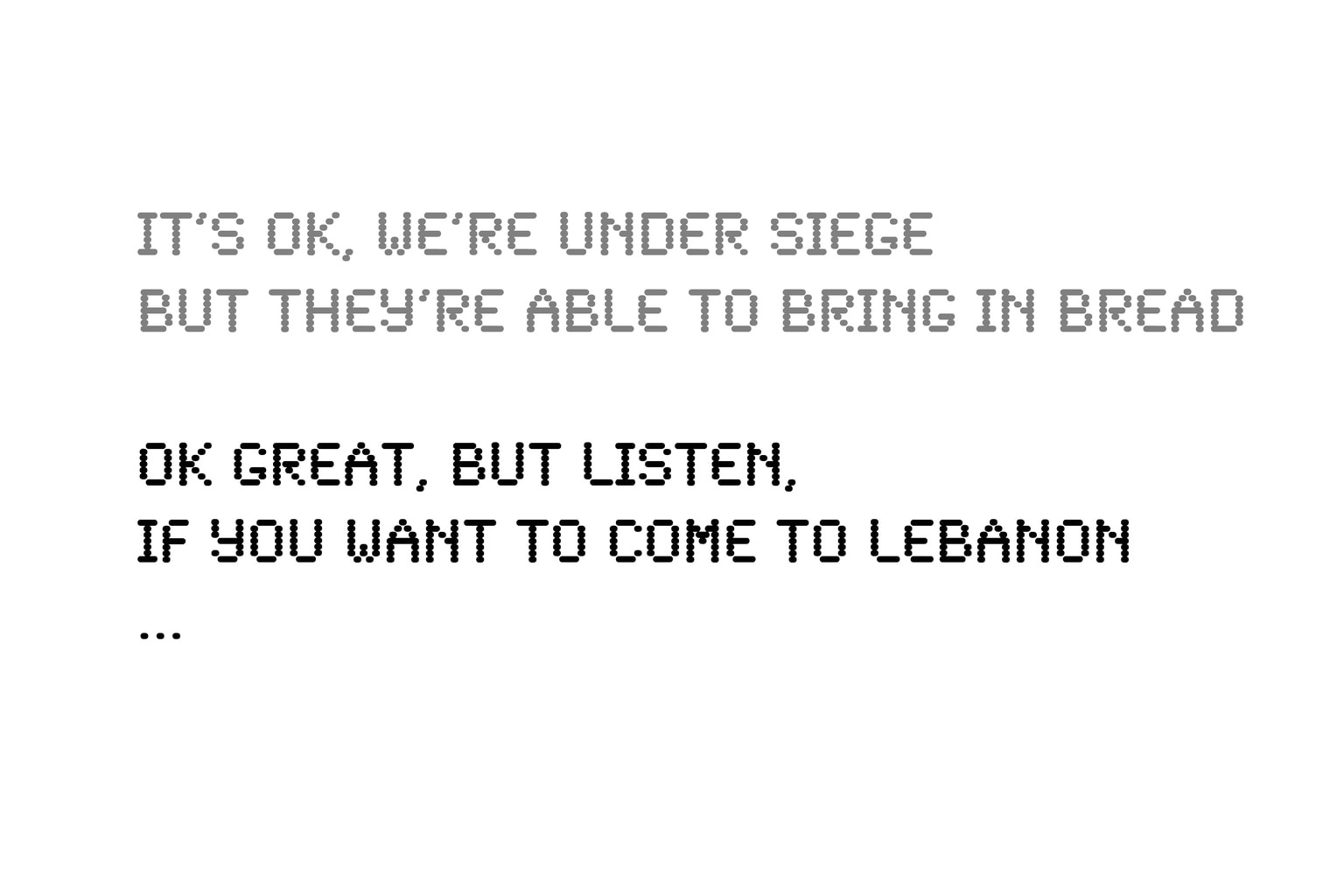

Once the photos were shot and the text messages translated, Liam puzzled out how best to convey his work—and that’s where our developer Daniel Arcé came in. A friend of Liam’s from Montreal, Daniel engineered a bot that allows viewers of Liam’s photography to receive the same text messages the refugees exchanged with loved ones on their personal devices.

In terms of tech, they needed to decide whether to set up and maintain their own texting server or go with a marketing solution like Twilio, which is already set up for a similar purpose. Daniel noted that initially, they had to convince the company that they weren’t a spam bot because the number of texts that they were sending was unusual. Scaling is extremely tricky with art pieces like this one, since there are no published metrics for similar work, and it can get expensive to maintain a constant pipeline. They then decided to use a company, Heroku, to actually handle the requests sent from Twilio after attendees of the installation text the phone number provided.

By directly connecting the subjects of his photos with their stories, Liam found a new way to make his work around this conflict that much more meaningful. Temporarily living the experience of receiving these messages while viewing the images of the refugees offers a visceral, physical sensation and provides a dimension of immersion that we as an audience would otherwise miss. Many of the texts convey a surprising combination of mundane chat and communications concerning life and death, reflecting the complexities of the everyday refugee experience. In a photography installation, the receipt of an urgent text message displaces the audience’s search for a feeling and replaces it instead with the feeling itself. This allows for an instant connection for the viewer to the image, strengthening the connection between the images and the lived refugee experience.

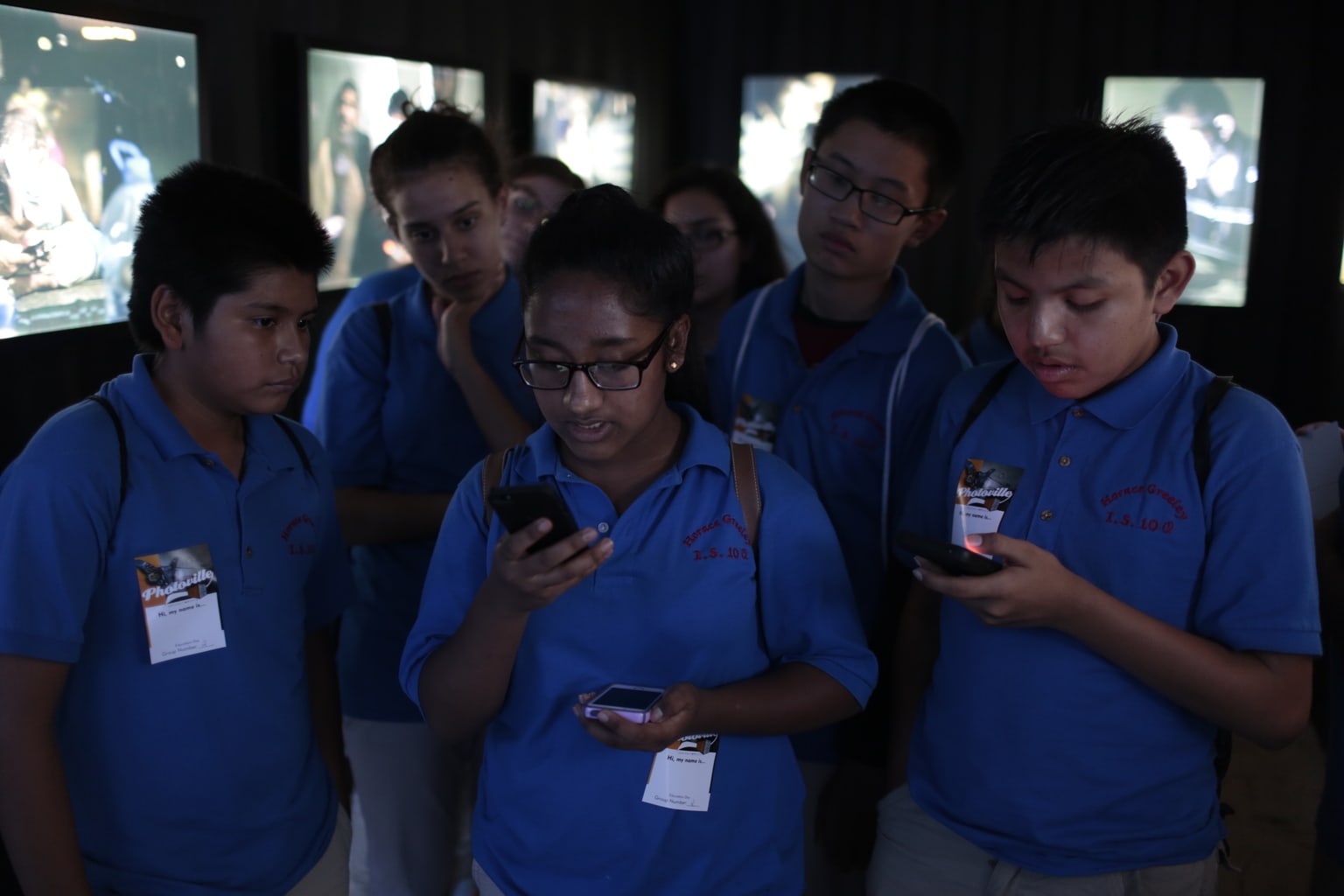

The public’s reaction to the interactive aspect of the installation is one of the most effective pieces of this project. The texts are hugely important to the photographs, so questions arose about how to scale the project for public consumption. Depending on their needs, Liam and Daniel can elastically add more “horsepower.” That’s been especially helpful when showing the piece at places like Photoville or The Nobel Peace Centre, which resulted in spikes in foot traffic.

Liam recounted that during Photoville 2016 a group of students came to see the piece and were mesmerized by the messages. The concept of using devices that would otherwise have served as a distraction to directly confront the students with the Syrian refugee experience is extremely moving. During his chat with us, he noted that he wants to move storytelling into the hands of the refugees themselves, not just famous photojournalists. Texting Syria is one highly effective example of this impulse in action. It begs the question: as more and more art is documented using mobile devices and spread on social media, how is our ability to ingest, digest, experience and relate to stories affected?

You can find more information about the work here and see more of Liam’s work on his PhotoShelter website.

All images by Liam Maloney.