Share

Richard Misrach Contemplates the Beach, Borders, and His New iPhone

In the age of Instagram, fickle photographers move from project to project in search of another “like” or follower. This perhaps explains why y...

In the age of Instagram, fickle photographers move from project to project in search of another “like” or follower. This perhaps explains why you won’t find the legendary American photographer Richard Misrach on Instagram, and why he’s been working on his heralded project Desert Cantos – a series of photos taken in the desert from a nascent Burning Man to the Utah Salt Flats to the U.S. Mexico border – since 1979.

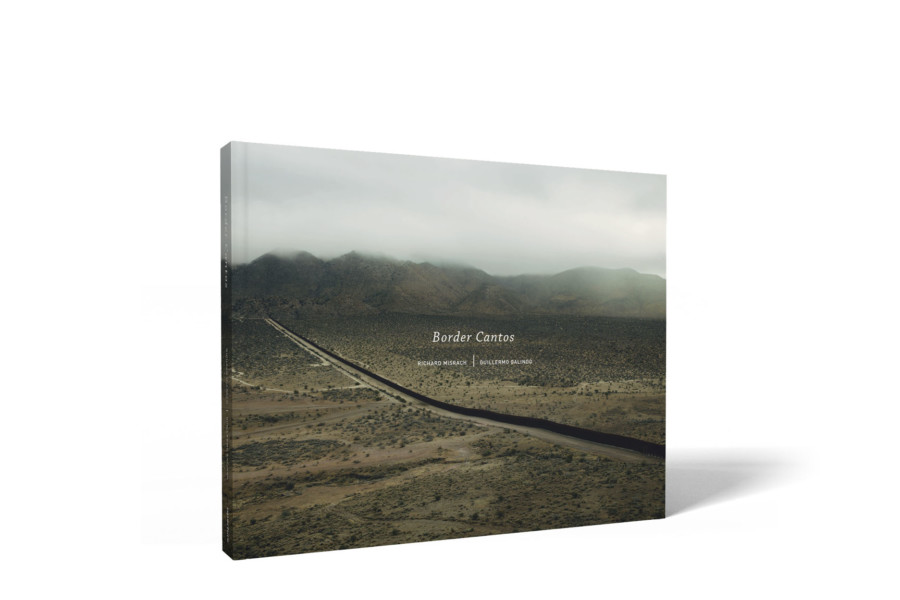

Misrach collaborated with composer Guillermo Galindo for his latest work entitled Border Cantos. An image from that series, “Romans 13:10” was presented by For Freedoms – an organization that seeks to use art to “deepen public discussions on civic issues and core values” – at Photoville 2019 in New York City this Fall.

As a long-time fan of his work, I was excited to interview him about the politically-charged nature of Border Cantos and the more serene images taken in Hawai’i for On the Beach.

***

As someone born in Hawaii, I’ve always been fascinated by On the Beach and On the Beach 2.0, in large part because of the near-birdseye view – a stark contrast from photographers like Massimo Vitali. What inspired you to shoot from up high?

The vantage point, from an upper floor of a beach hotel which I actually discovered by accident, provided a view unlike any I had had before. I thought of it as a “God’s eye view”. At the beginning (this was before drones), people thought I was shooting from a helicopter or an airplane. I kept it secret for a couple of years. I was actually shooting with a cumbersome 8×10” view camera, so the images were perhaps even more surprising. By simply cropping out the horizon line, the illusion of hovering directly above was achieved, even though the pictures are shot at a slight angle. And unlike shooting from the height of an airplane, I was close enough to get more detailed views.

What was amazing to me is the great variation of images I was able to get while staying in one spot. Previously, I had spent decades driving long hours across the deserts of the American West, chasing the light, searching for pictures. Here the discipline was the opposite. I stayed in the same place, and waited for the world below to change and offer up new pictures. At one point, I actually thought of naming the series “At the still point of the changing world” after T.S.Eliot. The universe was changing below me and all I needed to do was wait and watch and snap. That said, because of the events of 9-11, which haunted the early pictures for me, I ended up calling the series On The Beach (2002-2005).

The 8×10” film camera was brutally slow and cumbersome for photographing people in the landscape, but I wanted the great detail. It was the “wrong” camera for the project. For example, when I saw someone in the ocean doing a handstand, I’d rush and grab my camera, focus the scene on the ground glass, take a meter reading, set the aperture and exposure speed, grab a film holder, carefully slip it into the back of the camera, slowly pull the slide out, and then gently trigger the cable release. All this took nerve-wracking time. More often than not the person doing the handstand had swum off out of the frame. So many amazing pictures were gone before I could make an exposure.

In 2006, after almost 40 years of shooting film, I began using a high resolution digital camera which allowed me to work super fast, making multiple exposures in seconds, and I could shoot at faster speeds and stop action. I could even work in windy or stormy conditions when even a slight breeze would ruin an 8×10”s long exposure. And shooting the big film was expensive. By the time you factored in the film, development and contact sheet made at a lab, it was $20 every time you snapped the shutter. With digital files, there was none of that. You could make hundreds of exposures in an afternoon.

Working with a digital camera allowed me to make new kinds of pictures that simply weren’t possible before and with the same quality as an 8×10’ view camera! So I started another round of images from the balcony, which I called, On The Beach 2.0.

The series title is taken from the Nevil Shute book of the same name in which beachgoers are oblivious to nuclear disaster. Last year, Hawaii had a false incoming ballistic missile alert – did you suddenly feel psychic?

I hadn’t thought of that. Some dear friends in Hawaii went thru that missile scare and it was truly awful. But yes, there was a dark undertone to the origination of this series. I was in Washington DC on 9-11. My first impulse was to fly home, get my 8×10” camera and return to the East Coast. But I realized the place would be swarming with photographers, which would make my presence redundant. But I had to do something! I initially went to the desert thinking I might discover some response there . Nothing.

Then I went with my wife and friends on a previously planned vacation to Hawaii. That’s when I discovered the view. I was struck by the perspective and the scale of the figures to the larger sea around them. The people floating were seemingly in control, yet from my viewpoint I saw their vulnerability as a vast sea surrounded, practically engulfed them. Strangely enough, the views reminded me of the dreadful pictures I had seen of the figures leaping from the buildings on 9-11. There was something in those pictures conveying agency, an existential will in the face of that terrible moment as they were falling thru space. To me, these folks floating or swimming at sea were lovely, beautiful as they were enjoying themselves—but in my mind the scenes were haunted by recent events.

All that led me to think about the post-apocalyptic novel and Hollywood movie, “On The Beach”, which describes a moment after nuclear exchanges and most of the world has been destroyed. Australia is the last unaffected continent but a deadly radioactive cloud is heading there. People are aware that their days are numbered, and decide to live their lives to the fullest, picnicking and enjoying the beach. After 9-11, as we were bombing Afghanistan, what I saw below seemed like an analogy to the movie.

You’ve embraced the use of technology (digital cameras, smartphones) in your work. Have you considered the use of drones – perhaps On the Beach 3.0?

Good idea. But no. At least not yet. I’ve shot from this same spot for almost 17 years and I may have exhausted its possibilities. At least I’m not sure I can continue to work there much longer. Time to move on. But one of the amazing things about photography-proven true throughout its relatively short history—is every time there is a technological advance in the medium its very language gets profoundly expanded. It will be fascinating to see what kinds of pictures drones will enable.

You’ve been photographing along the US/Mexico border since 2004 with the intent of exposing the cruelty that Josh Kun says, “funnels the tired into desert bottlenecks and tracks the poor through gulches.” How has the rhetoric around “building the wall” and anti-immigration affected your thesis? Do you feel more urgency around this project?

The book and traveling museum exhibit were just being launched when Trump was running for the Republican nomination. The issues were all there, if somewhat latent in the public’s consciousness. With Trump, the political exploitation of the border has risen to new heights. Of course, this has increased attention to our project as well. Spinoff exhibitions from the original traveling museum show are scheduled for the foreseeable future.

I think the project holds up well . It is more of a meditation-rather than a definitive statement or political position—on the issues at hand. The ultimate question raised is still this: Is America going to be a safe haven for the desperate and endangered, or are we going to turn those people away and return them to an often terrible fate? America’s identity as a nation is ultimately at stake here.

Your photo Romans 13:10 (“Love does no harm to a neighbor. Therefore love is the fulfillment of the law.”) is pretty pointed and direct compared to most of your other images that are directional, but still leave ambiguity over interpretation. What was the impetus to include this in Border Cantos?

Indeed, in contrast to what I was just saying, the billboard I made for Forfreedoms, in advance of the 2018 election, was explicitly political. It was an attempt to appeal directly to the best of human nature, by pointing to the Bible, right before that election. I consider the larger project of the Border Cantos, the book, the exhibition, and especially the poignantly relevant and symbolic collaboration with Guillermo, to be an encyclopedic study of the border at our particular historical moment, that will speak to future generations. The billboard is for right now. Very different contexts.

Many people think of you as a large format 8×10 photographer, and when I learned that you were using an iPhone for some work, it almost seemed antithetical. What led to your adoption of the smartphone? And how does using it (both artistically and technically) compare to your 8×10? Do you obsessively await the new model each year like many consumers?

I haven’t shot 8×10 for 13 years. The cell phone camera is always with me, and is inconspicuous. I can photograph quickly, without drawing attention to myself. Hence, I am able to make a different kind of picture, impossible with either the big film or digital cameras. As I said above, with each new advance in technology, the very language of photography is expanded.

In my larger Desert Cantos project, I have always embraced various strategies and esthetics. Some of my series have been metaphorical, some explicitly political, others more theoretically or conceptually driven. By combining these different approaches, the Cantos inform each other and broaden meaning, and even draw attention to the photographic language itself (as your question in fact does).

Ezra Pound famously used seven languages, including Chinese ideograms in his fifty-year-long poem The Cantos. I believe that part of the effect of inserting all these languages into the heart of the poem is to stop the reader in her tracks and to make one aware of language itself. Similarly, I like drawing attention to all the methods we use—the cameras, film versus digital capture, color versus black and white—and how they self-reflexively impact our experience and understanding.

My most recent cell phone has been the [iPhone] 6 plus. I was just given the [iPhone] 11 pro and am about to take it out of the box. Wish me luck.