Share

On Ethics, The First Amendment, and Photographing Protestors’ Faces

During the short-lived daily White House Coronavirus Task Force briefings held by President Trump, a number of news organizations debated and ultim...

During the short-lived daily White House Coronavirus Task Force briefings held by President Trump, a number of news organizations debated and ultimately decided to stop providing live coverage. On one hand, his propensity to lie or provide specious information (e.g. injecting bleach) was counterproductive to the public health. On the other hand, the President is arguably the most powerful person in the world and so everything he says is “newsworthy.”

Newsroom directors and editors faced an ethical dilemma since falsehoods couldn’t be fact-checked in real-time and public health was at stake, plus his ramblings made many question the newsworthiness of the events. So a reassessment of the utilitarianism of live coverage was made – i.e. the potential for public health harm mattered more than the real-time coverage of the President.

U.S. Presidents have historically taken significant care in delivering their public statements. But Trump’s communication style has upended the norm, and necessitated a re-examination of press policies. Even still, critics assail the press for helping Trump by amplifying even his most controversial statements with some even arguing that the press is complicit in pushing misinformation.

***

A vigorous, sometimes vitriolic debate has erupted in photography circles around whether to photograph protestors’ faces. As someone who’s written about the topic, I’m struck by the clumping together of disparate concepts and issues, which has made discussion difficult. People are arguing, but they are often arguing about different concepts simultaneously.

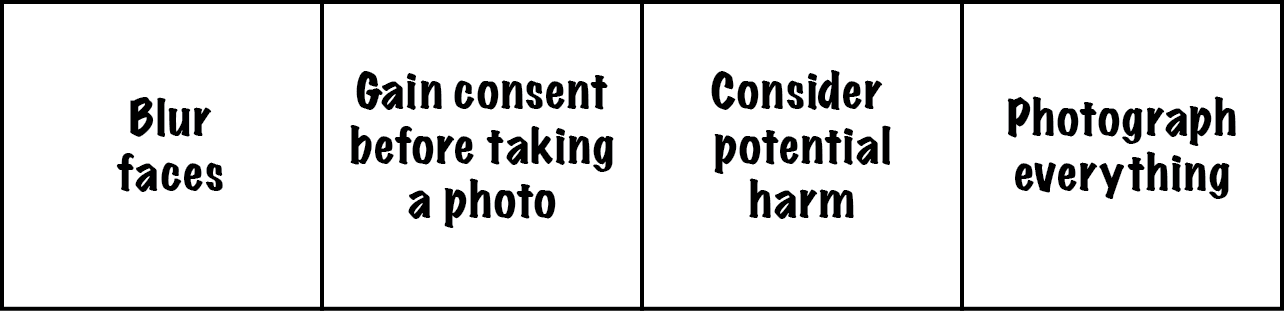

I categorize the different arguments into four camps of thought:

- Blur faces

- Gain consent before taking a photo

- Re-consider potential harm

- Photograph everything

The categories aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive – after all many photographers consider the well-being of their subjects. And the descriptions are necessarily reductive for illustration purposes.

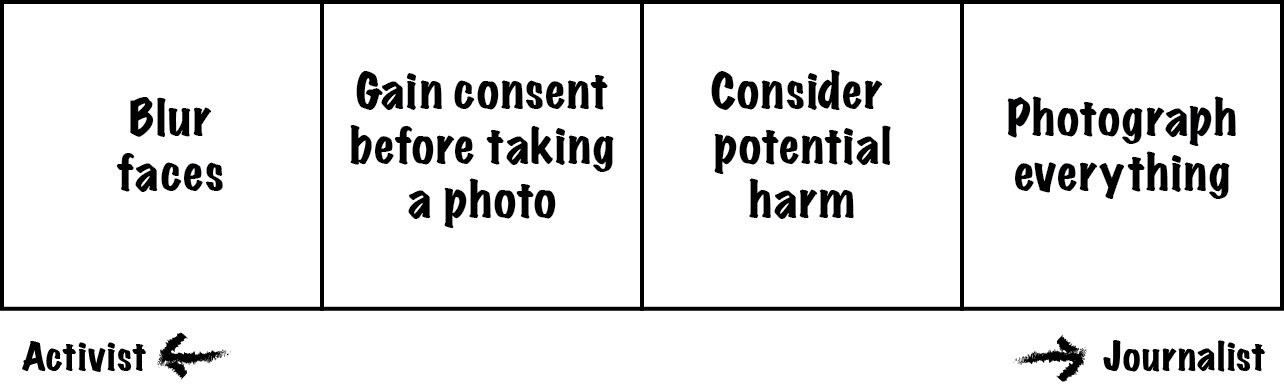

The spectrum effectively moves from maximum concern for the subject on the left to maximum concern for freedom of the press on the right, which can also be interpreted as the following:

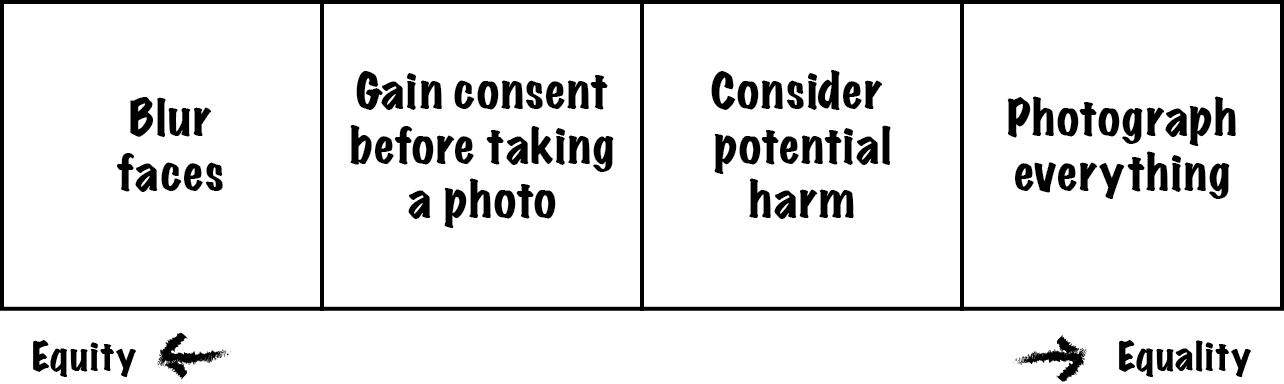

From an equity/equality standpoint, the spectrum could be visualized as such:

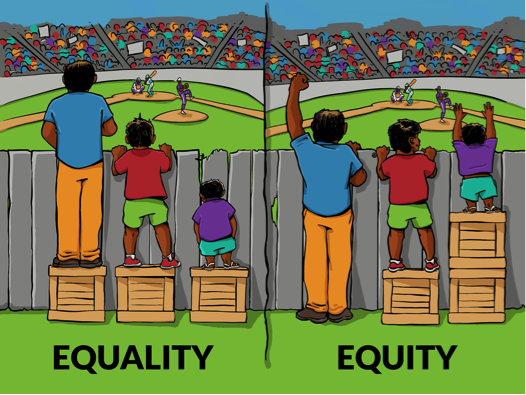

Photojournalists have often invoked statements like “we cover white nationalists the same way that we cover victims of racism.” The point being that by treating everyone the same, they maintain neutrality, and build trust and legitimacy. Equality equals fairness.

By contrast, some activists argue that the oppression of African-Americans requires different treatment. The argument isn’t historically spurious (e.g. slavery, Jim Crow laws, police bias), and we continually see filmed incidents of “walking while Black”, “birding while Black” which shows how black and brown citizens are treated unequally both in the eyes of fellow citizens and law enforcement. Equity equals fairness.

Both equity and equality are fair under different frameworks. This is a crucially important point to be aware of while discussing these ethics.

There is a huge lack of understanding by the general public around the role and function of the press, which isn’t surprising given the 1) demonization of the press by President Trump, 2) reflexively blurting out “first amendment” in any disagreement about “freedom,” and 3) lack of civic education in this country.

The conflation of concepts like protecting a protestor’s “rights” to protecting a “source” is indicative of a basic misunderstanding of journalistic ethics and First Amendment rights. And to complicate matters, some protestors are arguing with photojournalists, some photographers are arguing with photojournalists, and some photojournalists are arguing amongst themselves over questions of how news should be captured.

Ethics vs Journalistic Ethics (Normative vs Applied)

Ethics describe a philosophical framework to consider right and wrong. Normative ethics is the branch we largely talk about in civic and religious life. The “runaway train” scenario explores utilitarianism – should you kill more people to save the pregnant lady (or the doctor or other variants)?

Journalistic ethics falls under the branch of applied ethics. The NPPA’s Code of Ethics outlines commonly agreed upon standards of photojournalistic behavior which include everything from “Resist being manipulated by staged photo opportunities” to “Do not manipulate images.” But there is no single standard of journalistic ethics, and standards can dramatically vary by country. These applied ethics are simply what journalists are supposed to be taught or absorb through osmosis.

Journalistic ethics also encompass a concept like source protection. There is no federal shield law (and state statues vary in what they cover), but it’s commonly accepted that journalists will protect a confidential source (with some willing to go to jail to preserve this sanctity). This willingness is both ethical as it is practical – if you give up sources, you’ll never have future sources. And journalists generally don’t want to bring harm to their sources.

When it comes to photography, the public largely operates with normative ethics. I can go to a public park and photograph children, but cultural ethics (aka courtesy) usually compel me to ask permission, or stop when asked.

Journalists performing news functions operate under a different set of ethics – a set that the public is largely unaware of. Most photojournalists don’t have an agenda when they go out and shoot, but the public’s experience and understanding of photography is that it is personal and sometimes subject to abuse (e.g. weaponization of photography). The public can ask a photojournalist to stop taking photos of a child in public, but they cannot legally prevent it.

There is no legal penalty to breaking an ethics rule. You might lose friends if you’re unethical, but you won’t go to jail. News organizations won’t hire you if you manipulate a photo, but you aren’t prevented from taking a photo and you won’t go to jail.

It’s also very difficult to argue applied ethics of a specific industry against normative ethics of a society. Medicine is full of ethical issues that often require medical expertise to contemplate the nuance of a particular case. Similarly, the average person usually doesn’t understand the limits of post-production in news images – often assuming that “Photoshopping” is occurring anyway.

The First Amendment

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

Congress can’t create laws to abridge the freedom of the press. In public spaces, it’s incontrovertible that the press and anyone else can take your photo (usage is another matter altogether). It might fly in the face of your ethical framework, but no law can be created to prevent a picture from being taken of someone within a public space.

I’ve read many photojournalists vehemently defend their First Amendment right on social media, and prioritize this right over normative ethical concerns. The decimation of the industry – both at the hands of unscrupulous owners, and changes wrought by technology – have made it vital for journalists to continually pound upon their First Amendment right. Their very survival is at stake.

Many people abhor paparazzi, but they have the same legal right to take photos in public. Their methodology flies in the face of journalistic ethics, but the public’s interest in celebrities makes the photos “newsworthy” to many. What’s good for the goose is good for the gander.

Ethics evolve

The only immutable in this “debate” is the First Amendment. But society can’t function with laws alone, and so we rely on social mores and ethical frameworks to guide our day-to-day activity.

Acceptable behavior evolves over time, and so journalistic ethics have also been subject to a changing understanding. For some photographers, Steve McCurry’s legacy is tarnished by allegations of scene and post-production manipulation. For others, it’s the imperialist gaze. In either case, the evolution of ethics has caused a re-examination of his work.

The NPPA’s Code of Ethics is intentionally vague, and without regular discussion about how it applies to new technologies and new scenarios, it’s in danger of being a fossilized document. For example, compositing of images is prohibited by most news organizations unless labeled as a photo illustration. This is why stitched panoramas don’t qualify as news images. But the newest camera phones (e.g. iPhone 11) use computational photography in low light to composite multiple shots into a single image (i.e. Night mode). Yet, I haven’t seen any discussion around using the iPhone as a source of news photography (and yes, it’s being used by “real” photojournalists).

The use of facial recognition by LEO comes up again and again as a concern for not showing protestors’ faces. Many photojournalists push back against this concern by pointing out the numerous cameras in everyday life (and those set up specifically by LEO). Some also point out that the abuse of images isn’t a photojournalism problem, it’s a police problem. This is true.

But photos with wide circulation can be memed, and depicted people can be doxxed and threatened. Technology and social media can and will continue to cause harm, so it’s not unreasonable for photojournalism to re-evaluate the concept of “harm” with a 2020 lens. Visuals can reach more people, more quickly at no cost. It’s not the responsibility of photojournalism to solve this problem, but it’s also naive to refuse to consider unintended consequences.

This is the time to talk ethics

In the same way that the murder of George Floyd has once again forced many Americans to re-evaulate subjugation of African-Americans, photographing the protests has provided an opportunity for photographers of all genres to consider the role and purpose of photography.

Photojournalists don’t want to be lectured by activists (rightfully so), and activists don’t want to be lectured about the First Amendment when they see an uneven application of the law. A periodic re-examination of ethics in light of technological and societal change should be embraced.

To me, the real discussion shouldn’t be about the blurring or obscuring of faces, nor gaining consent of a subject. These are tactical choices, and in the U.S. there is simply no expectation of privacy in a public setting.

Instead, we ought to continue to consider how photography is used to portray others (particularly the vulnerable), and whether an image truly advances a story or simply acts as a signifier for the photo we should have taken.