Share

Lynn Goldsmith’s Victory Against the Warhol Foundation is Huge for Photographers

In 1981, Newsweek hired photographer Lynn Goldsmith to photograph Prince, an up-and-coming musician who was still years away from releasing his sem...

In 1981, Newsweek hired photographer Lynn Goldsmith to photograph Prince, an up-and-coming musician who was still years away from releasing his seminal “Purple Rain” album. Goldsmith’s portraits never ran, but she did own the copyright.

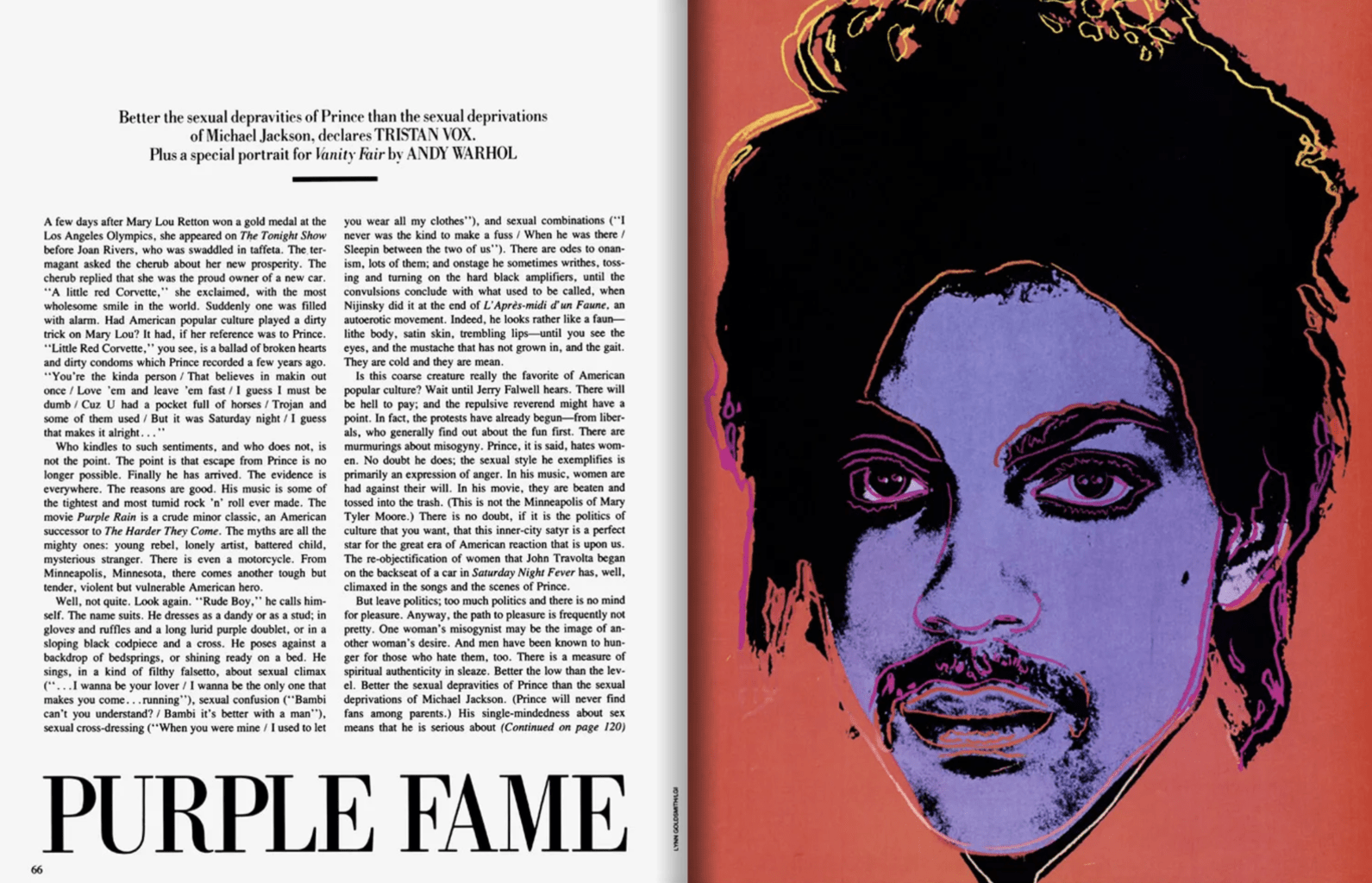

In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed one of the images as an “artist reference,” then commissioned Andy Warhol to create an illustration based on the photo for a piece entitled “Purple Fame: An Appreciation of Prince at the Height of His Powers” (The piece attributed Goldsmith). Warhol subsequently created his “Prince Series” – an additional 15 artworks images based on Goldsmith’s photo.

Upon Prince’s death in 2016, the Warhol Foundation licensed the Prince Series for use in a Condé Nast tribute magazine, and one of the images was used on the cover. Goldsmith tried to extract a licensing fee, but the Foundation accused her of a “shake down” and filed a pre-emptive lawsuit in 2017. The suit sought a “declaratory judgment” that Warhol’s images didn’t infringe upon Goldsmith’s copyright and were “transformative or are otherwise protected by fair use.” Goldsmith countersued for infringement.

In 2019, Judge John G. Koeltl ruled against Goldsmith in U.S. District Court stating that the artwork “is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince.” Goldsmith appealed the decision and it was sent to the 2nd Court of Appeal.

On March 25, 2021, the 2nd Court of Appeals reversed the 2019 judgment by weighing four factors of the Fair Use doctrine as outlined in Section 107 of the Copyright Act. It found that “each favors Goldsmith.”

The Court disputed the notion that the works were transformative stating that Warhol “produced the Prince Series works by copying the Goldsmith Photograph itself – i.e., Goldsmith’s particular expression of that idea.” The Court also disputed Judge Koeltl’s aforementioned claim of recognizability as “entirely irrelevant” writing, “entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege.”

Further, the Court wrote “Fair use, when properly applied, is limited to copying by others which does not materially impair the marketability of the work which is copied.”

Photographer and PLUS Coalition President Jeff Sedlik served as Goldsmith’s expert witness in the case, testifying on fair use, derivative works, and business models in the photography industry. As the matter is ongoing, Sedlik declined to comment specifically on the matter. About licensing, Sedlik explained that “Photographers are in the business of licensing their copyright to others – including licenses to fellow artists to create derivatives. When an artist creates a new work based on a photograph without authorization, the artist robs the photographer of the license fee normally applicable to ‘artist reference’ use, and any damage to the market for licensing the photograph to others. As the owner of the exclusive rights in a work, the photographer has the sole discretion as to the timing, nature and scope of each license, to each licensee, for each type of use. Photographers will often withhold licenses for years – even decades – in order to increase the value of their copyright assets.”

The Warhol Foundation sought to license the artwork for an editorial purpose, which directly competes with how Goldsmith uses her photography. The Court wrote “In short, the evidence plainly establishes that the Prince Series has acted as a market substitute for Goldsmith’s photograph.”

It’s important to note that the Court referenced its own decision and logic in the well-known Cariou v [Richard] Prince case, in which 25 of 30 of the images in question were deemed sufficiently transformative. And it also didn’t dispute the earlier Court’s ruling that the primary markets for Warhol and Goldsmith’s work “do not meaningfully overlap,” so the ruling doesn’t mean that appropriation art suddenly became illegal. But the interpretation of the ruling might affect pending lawsuits against, for example, Richard Prince for his “New Portraits” Instagram series.

The Warhol Foundation has vowed to appeal the ruling. And the Supreme Court would be the next and final avenue for appeal.

In a statement released through her attorney Thomas Hentoff of Williams & Connolly, Goldsmith wrote, “I fought this suit to protect not only my own rights, but the rights of all photographers and visual artists to make a living by licensing their creative work—and also to decide when, how, and even whether to exploit their creative works or license others to do so.”

Goldsmith created a GoFundMe to defray her legal costs.