Share

Photographing the 10 Year Anniversary of Japan’s Fukushima Nuclear Accident

On March 11, 2011, the 4th largest earthquake since the advent of modern record-keeping struck off the coast of Japan generating a tsunami that inu...

On March 11, 2011, the 4th largest earthquake since the advent of modern record-keeping struck off the coast of Japan generating a tsunami that inundated the coastal Sendai area. Nearly 16,000 people were killed and another 2,500 went missing. Three nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant suffered meltdowns spewing radioactive material into the region, and ten years later, many areas are still uninhabitable.

Photojournalist and Founder of @everydayclimatechange James Whitlow Delano has lived and worked in Tokyo for decades, and has covered the disaster, its aftermath, and the glacially slow rebuild. For the 10th anniversary of the tragic event, Delano created a haunting photo and video package for the New York Times. I reached out to him via email to learn more about his experiences.

This interview was lightly edited.

Allen: I was two blocks away from the WTC on 9/11 when the first tower collapsed, and have very vivid memories of that day. Can you tell me what you were doing on 3/11 and the thoughts that went through your mind as the tragedy unfolded?

James: Oddly, I was finishing up travel in Italy exhibiting and talking about work done in the Malaysia rainforest. I was slumming it in a small pensione near the Rome Termini Station, without television or internet. I called my wife, who is Japanese, on a burner phone. I was flying out that morning. She was astonished I had not heard the news. I literally ran to the nearest internet café (they still existed then) and began watching footage of the tsunami.

I immediately hatched plans to head north with photographer friends in Japan – before I even got on the plane. It turned out, because of the meltdown at Fukushima Daiichi, it was one of the last inbound flights to Japan. I landed in Tokyo at 2pm and by 2am we were on the road north. We headed for the far Sea of Japan coastline, knowing that roads to Tohoku on the Pacific side were impassable and there were rumblings about a coming meltdown at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. We had a mountain range between us and the plant. The moment we crossed the mountains in Akita Prefecture, supplies had been cut, food shelves were empty, gasoline lines lasted for days. We hired a taxi that used natural gas as fuel because LNG was plentiful. Driving down to the tsunami zone, we entered a scene of snow falling on people who were shuffling around in a daze, cars lifted by the tsunami and set down to be suspended on wires, bent around poles and we joined that legion of people trying to figure out what had happened.

Allen: You covered Fukushima five years ago for NatGeo. What changes, if any, did you make in approaching this assignment?

James: I started covering Fukushima in April 2011, after a month of this child of the Cold War, warily coming to understand the nature of the radioactivity. At that time, I received an assignment for Der Spiegel. The Japanese government had set up stations measuring radiation around the periphery of the 20 km (12.4 mi) nuclear no-entry zone. We carried a Geiger counter and discovered that the government measurements matched our own. If you sat outside in Fukushima City, at that time, naked, 24 hours a day, for two weeks, you would receive roughly one extra x-ray. I determined I could live with that.

Some other places in the mountains, at that time, directly downwind and outside that arbitrary the 20 km radius of the no-entry zone, radiation levels were through the roof. So, we learned where we could go safely and where to avoid.

The changes I made for working were just that, documenting areas inside and outside the zone in areas I knew had lower radioactivity, and I got my work done and left. Evacuated towns look the same whether they are highly radioactive or not too bad, relatively speaking. By five years ago, many communities on the northern and southern coastal fringes of the no-entry zone had been opening incrementally as the government went from the arbitrary no-entry 20 km radius to a system of closing areas based on their level of radiation. There was one place, Tsushima, that is in the latest body of work, that I could actually visit early on in 2011 (very briefly) and then, a few months later, it became part of a reconfigured no-entry zone.

Now there are roads cutting straight through the heart of the no-entry zones that are accessible by car. Pedestrians, bicyclists and motorcycles are forbidden from entering. I drive throughout that area and document from the road or by drone, again, very briefly, what bucolic communities look like after a decade of nature reclaiming them.

Allen: The New York Times hired you to take photo and video of the area. Can you describe how the job came about, what was on the brief, and how long you spent on the assignment?

James: Well, this is an interesting situation. I went to Fukushima, because of the impending anniversary, funded by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. It is not hyperbolic at all to say that my most important work over the past decade from Malaysia, to Mexico, to Bolivia has been made possible through funding by the Pulitzer Center.

When I approached the New York Times with that series I made in December/January I already had commitments to publish that work in Italy (L’Espresso) and in Germany (Süddeutsche Zeitung).

The New York Times liked the work but declined because they wanted work made specifically for their publication. We hatched a plan for me to return to Fukushima to photograph the series for them. It was a dream assignment. Photo editor, Mikko Takkunen was already familiar with my work. We had worked together on a couple of stories already and he invested trust in me. Based on our conversations, he let me know what he/they wanted to learn about Fukushima but, ultimately, I was given wide latitude to follow my reportage instincts on a six-day assignment. Being intimately familiar with Fukushima, and its post-disaster history, I was able to move around the zone quickly.

Allen: Did you have to take physical precautions to enter some of the areas (e.g. radiation monitors, suiting, etc)?

James: I was masked at all times and knew well where there was elevated radiation. That said, hotspots exist, often where water pools or by chance where the wind had driven the fall out. So, while in the zone, I never lingered in one place too long. In general, the mountains, and along the foot of those mountains, acted like a net capturing fall out. The forest tends to harbor more radiation. Also the other long term issue is that every time it rains or the snow melts, water draining from the mountains and forests delivers radioactive compounds into areas that have been decontaminated.

All this said, much of the former no-entry zone has only slightly elevated radiation levels but that still fall within the parameters of normal by globally standards but higher than, say, Tokyo. There are solar powered Geiger counters installed periodically through the area around the plant. The question is always going to be, if you walk around a property or between properties, how much can you trust that the land was truly decontaminated. Are there hot spots?

Frankly, at this point, Covid-19 was more of a concern and factor in my planning. Usually I would take the shinkansen bullet train to Fukushima City and then rent a car but, this time, I drove a car rental up from Tokyo. I did not eat in restaurants and, instead, endured three meals a day out of convenience stores. I made sure that the windows in the hotel could be opened and I made sure that the elevator was empty before entering.

Fukushima is rural and it felt like being released from prison. Most of the zone sits on the coastal plain called, “Hamadori” or “Coastal Road/Route”. The skies are wide and, in wintertime, cobalt blue. I am from California. You have the blue sea, sandstone cliffs, reminiscent of California and the gold reeds simply explode with color. If it were not for the radiation, honestly, I would love to live there.

Allen: When did you start incorporating drones into your work, and how did you conceptualize the drone shots for this assignment? Did you need to obtain permits?

James: I bought a drone in December. With a 48 megapixel still camera, and 4K video, I knew it was the perfect tool (DJI Mavic Air 2) to access those vast expanses of Fukushima unattainable on foot. I did not want it to be a “drone” assignment but rather to use a drone to photograph what I wanted to photograph but, otherwise, could not. I was mindful for the drone stills, in particular, to blend them in, as seamlessly as possible, with the stills made on the ground. In other words, I wanted it to be employed to enhance access, not to be used as a new gimmick. What I loved most was how it exposed the unseen textures inside of which we live but are unaware of.

In Japan, you do not need a permit to fly a drone. There are no-fly zones that you must be aware of. Tokyo is basically one big drone no-fly zone but the countryside is fairly wide open as far as the skies are concerned. There is a no-fly zone over Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant but it is surprising how closely it adheres to the plant’s property. DJI has an online map that lays out no-fly zones.

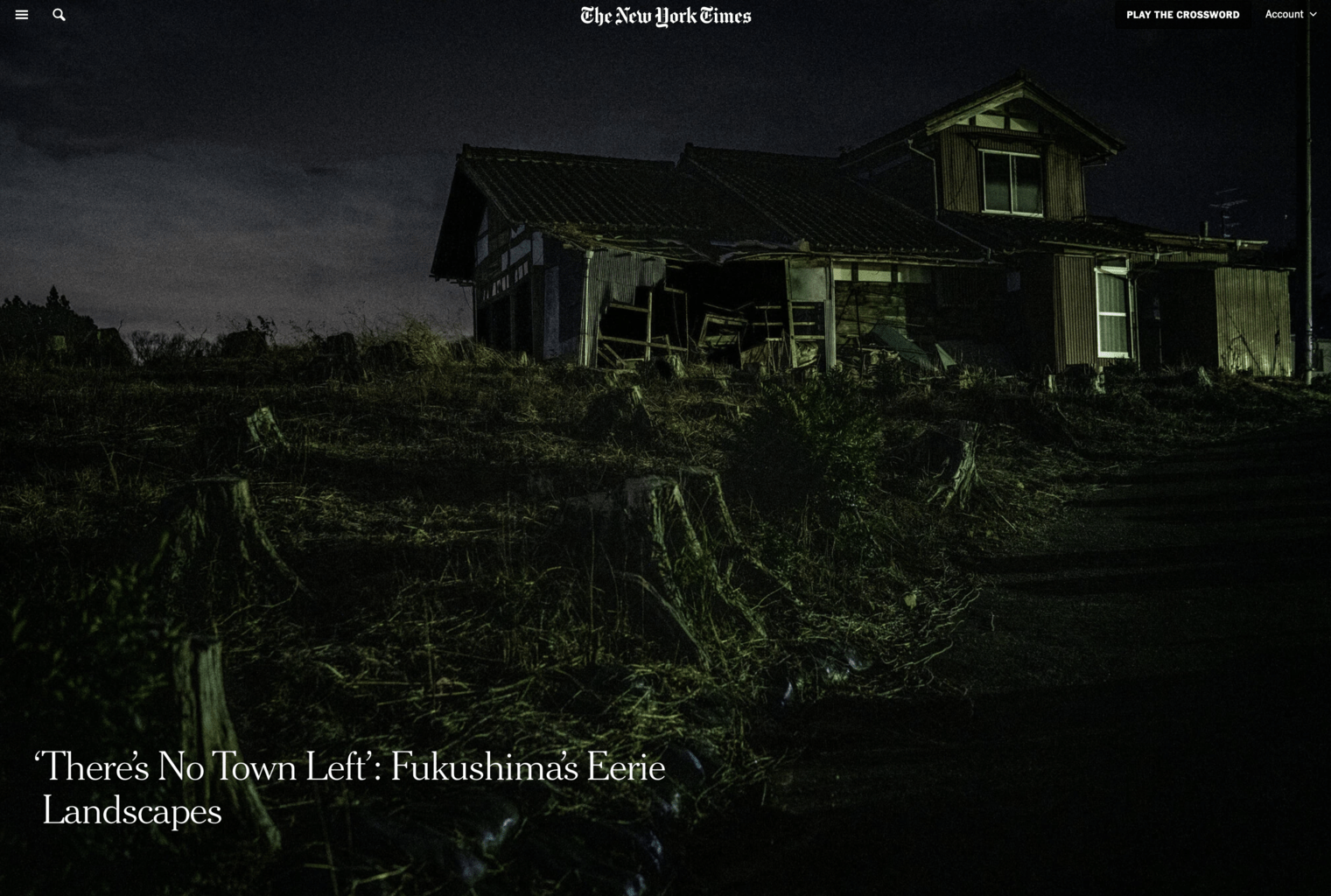

Allen: I was struck by the number of night photos that ended up in the essay. Why do you think they are so effective in communicating the story?

James: To me, the unifying theme is lost histories – happy times, centuries of them, silenced, hopefully temporarily. At every turn in the road, I imagined children playing, people growing old together, people pausing and thinking how lucky they were to live in such a lovely place. Then I would either see no one, or construction workers or perhaps seniors who simply came home because they wanted to live out their final days there. That said, it was not the same. In most of the towns, there are no young people, no young children at all and vast vacant lots.

I felt that the night communicated that feeling and in Futaba, in particular, it did not come without risk. Futaba feels raw. It just opened but it is still unoccupied and overgrown but patrolled by watchful law enforcement. Rare is the house has not been broken into. The final photo of the mini-van, was one of the most stressful images I have ever made and that working in Afghanistan or documenting Duterte’s so-called “War on Drug” and all the extrajudicial killings.

I returned to Futaba one night to make that image, knowing that it was down a lonely, unlit alleyway, and surrounded by houses that had been broken into. So, there I was, a foreign man, dressed in black, in a dark alleyway with a tripod and camera.

Also, from a practical perspective, the dark houses communicate, better than anything else, that their inhabitants have not returned a decade after their hasty evacuation. So, in all of the photographs the viewer can imagine, what if this happened to my own family, my own town – perhaps where my family has literally lived for centuries? We are all one very bad day away from having our lives deeply disrupted and if we feel empathy for others, we all benefit. I think Covid-19 has made that concept easier for a lot more people to grasp.

Allen: As a long-time advocate for environmental and climate-related issues, how did it feel to be in an area where fallout was still rendering large swaths of land uninhabitable?

James: This question underlies all the work I’ve done there. When we talk about a warming climate and the climate crisis, renewables loom large in that discussion and there are a surprising number of climate advocates that are pro-nuclear power. The work raises the question: at what cost? Interestingly, there are large solar farms now in Fukushima because the soil is too radioactive to farming. That is encouraging. Fukushima, and the displaced families driven to the winds, make clear that nuclear power, in its present form, is not the answer.

I have read about other forms of nuclear power in development, like “molten salt” reactors that are far less prone to meltdown but I am sure that the devil is in the details and, besides, apparently we are decades away, at best, to such a reactor coming online. The planet simply does not have decades to reduce carbon in the atmosphere.

So, to me, Fukushima endures as cautionary tale and, remember, it could have been a lot worse.

All images Copyright © 2021 by James Whitlow Delano.