Share

Indigenous Photographer Pat Kane Captures His Remote Hometown during COVID-19

Last year, as the COVID pandemic crisscrossed the globe and scientists were still learning about the disease and treatment options, many smaller co...

Last year, as the COVID pandemic crisscrossed the globe and scientists were still learning about the disease and treatment options, many smaller communities with limited medical resources were faced with the daunting process of shutting their borders to outsiders to protect their vulnerable.

In Canada’s Northwest Territories, the capital city of Yellowknife – home to a majority Indigenous population – set up the country’s strictest quarantine measures to protect its elders. The decision was driven by both practical concerns over resources as well as historical concerns over introduced diseases that ravaged and decimated indigenous populations in the past.

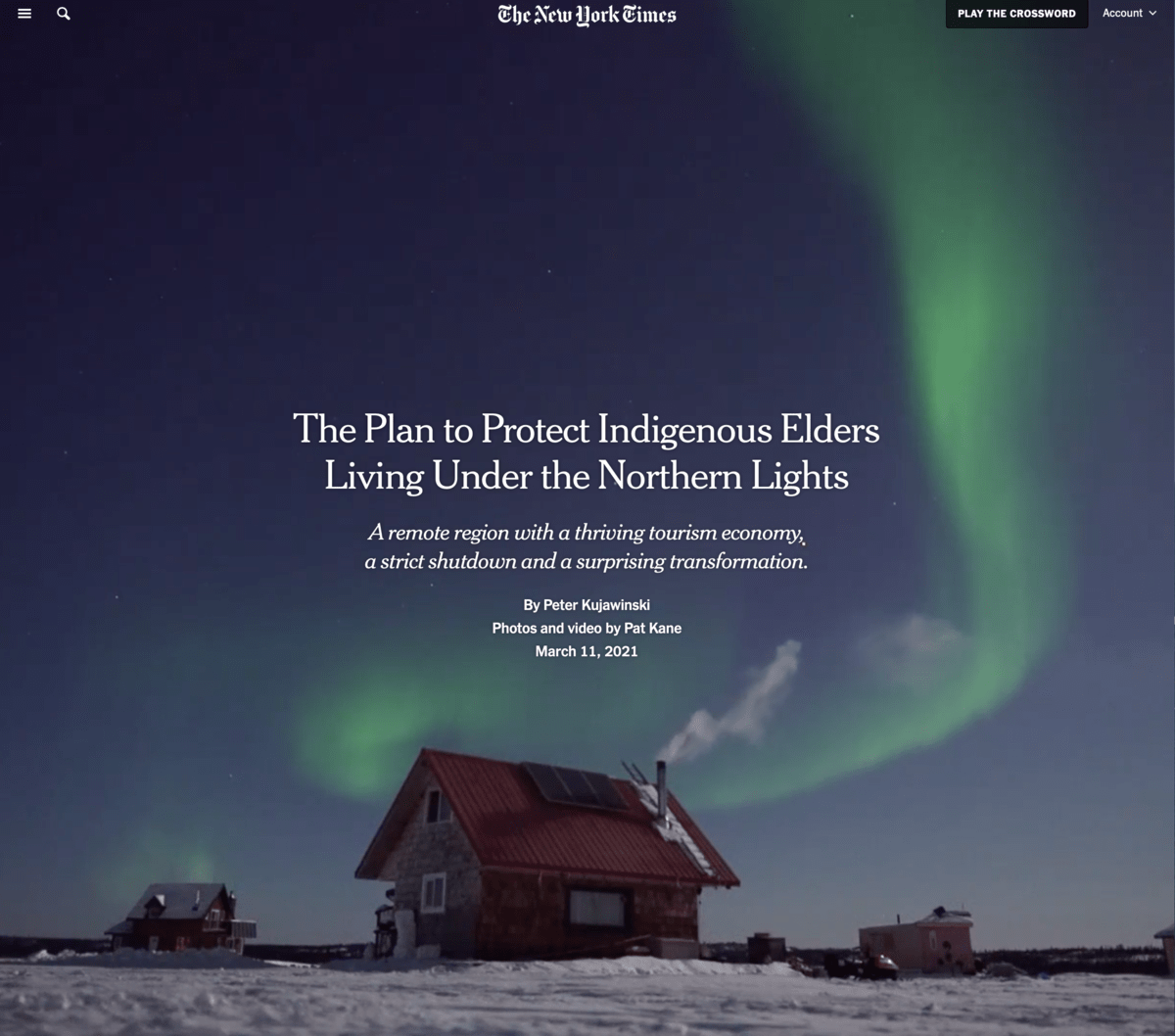

Indigenous photographer and Yellowknife local Pat Kane was hired by The New York Times to work with writer Peter Kujawinski to document the on-going story in a thoroughly engaging package entitled “The Plan to Protect Indigenous Elders Living Under the Northern Lights.” Kane is a member of Indigenous Photograph and Boreal Collective.

We spoke via email.

PS: You started taking portraits very early on in the pandemic when Yellowknife closed off access to visitors in order to protect the elderly. What was the genesis of that project, and how did it evolve over the past year?

PK: My portrait series early in the pandemic came about a few ways. The first was that I, like most photographers around the world, lost some jobs that I had lined up. With nothing to work on and adjusting to our new reality, I wanted to document how this global event was impacting the people in my community. My wife jokingly suggested that I become a family portrait photographer and take photos of people through their windows and I actually thought “hey, that’s a terrific idea!”.

I did a few of them and posted on Instagram and soon a lot of other photographers around Canada were following suit and it kind of snowballed into this larger thing. I think what made mine different was that I wasn’t doing portrait sessions in a traditional family photoshoot sense, I was trying to do it as a photojournalistic pursuit and as a way to document the pandemic in Northern Canada. We are outdoors people – nature and the environment is part and parcel to who we are – and everyone is extremely social and interconnected with our communities, so it was surreal to suddenly be cut off from each other and stuck in our homes or being physically distant.

We also knew how vulnerable our elders are, especially those in small, remote communities with extremely limited healthcare infrastructure. This idea of banding together for our communities was a beautiful story and one that was sharply contrasted against the anger and division I was seeing in the United States at the time and certainly as the pandemic went into the summer of 2020. I felt it was important to show how communities can do great things when they look out for each other. This has been the main focus of my work for the past 12 months now, starting with a short doc for The Atlantic, a National Geographic Society grant and this most recent story for The New York Times.

PS: How did the NYT find you, and what was the brief like? How many days of shooting are represented in the package?

PK: Around mid-January, writer Peter Kujawinski reached out to me from a generous recommendation by Alaska photographer, Chris Miller. Peter was looking to pitch a story to The New York Times about Yellowknife’s tourism industry and how Covid-19 impacted businesses and residents. For those who don’t know, Yellowknife is probably the best city in the world to view the aurora borealis, also known as the Northern Lights. We chatted for a while and I think Peter was surprised to hear that since our initial lockdown, strict travel restrictions and slow reopening, that we’ve actually been living a near-normal life compared to most places in the world. We also talked about my window portraits series and how people here banded together to protect elders and the most vulnerable. From there, the story evolved from a travel/business story to a much more robust story of resilience, Indigenous worldviews, healthcare and a rare success in fighting Covid-19 – all set against the backdrop of a wintery Northern Canada.

When Peter pitched the story, the editors thought it would be a good fit for their “From Here” series, which highlights how communities are coping with the pandemic. Coincidentally, I had just met with photo editor Amanda Webster during a portfolio review a few months prior and it just so happened that she was the photo editor on the “From Here” series. Amanda contacted me about Peter’s pitch and gave me the news that it was greenlit, so we took it from there.

The brief was that I needed to shoot both photo and video and that it was going to be highly visual. I received a few examples of previous stories and understood what they were looking for and what I wanted to shoot right away. After some initial meetings with the rest of the editorial team, Peter and I planned a rough outline and I began shooting Feb 18 and wrapped shooting on Feb 28, so it was a 10 day shoot altogether.

PS: How did you conceive of and plan the photo vs video portions of the package?

PK: I don’t consider myself a filmmaker or even a videographer, even though I’ve done many video and multimedia projects. I find shooting video to be technically overwhelming, time consuming, requires a different way of thinking, and generally, is just a pain in the butt. I met with Jonah Kessel, the cinematography director with the Times, Amanda, and Marcelle Hopkins, the creative director, to hash out a rough shot list based on Peter’s pitch and outline. I also met with Peter to develop a narrative structure, key themes and people we wanted to profile. For example, we wanted to 1) establish Yellowknife and the tourism aspect of the story, 2) how we locked down when Covid hit, 3) why those decisions were made and who made them, 4) how the Dene worldview of “being on the land” was important to physical and mental health, and 5) end by showing that the protections worked. I think because I understood the story so well and know all of the key players that the logistics of shooting and the kinds of content I needed to get was actually really easy.

When it came to physically shooting, that was another story. I would literally have my Nikon stills camera in one hand and a Sony video camera in another, or at least right beside me. I know now that this is NOT the way to do it, but I tried to match the stills I was shooting with video, and vice versa. This was probably the toughest part of the assignment. As a photographer, I like talking to the people I’m photographing and I try to capture subtle moments or gestures or nuances, whereas in video, you’re trying to shoot peak action and movement. It was a juggling act dealing with all this camera gear and shooting things simultaneously. On one of my shoots I started laughing at myself because I had a Nikon in my hand, the Sony on a tripod beside me, a GoPro on a dog musher and I was trying to fly a drone. I felt like such a nerd. What’s worse, it wasn’t helping me get better shots. From that point on I started to make better decisions on when to shoot only video and when to shoot only photos. I would leave one camera in the car sometimes just to resist the urge to shoot both. It was definitely a learning experience.

PS: How involved were you with the final edit?

PK: The story was 100% a collaborative effort. I wasn’t expecting to be as involved in the final edit as I was, to be honest. Peter and the editors at the Times were incredibly gracious when I had feedback or ideas. In many ways, I felt responsible that we got it right because I was the on-the-ground person and also the one who knows the lay of the land, the people and the story we were trying to tell. I think the editors were appreciative that I could help them navigate it and I felt a lot of ownership with the piece. Funny enough, most of my involvement was with the narrative aspects and some copy editing and helping Peter with names or contacts when he needed it. On the visual side of things, I trusted the editors to do their thing and put together a beautiful story that highlighted the important topics, which they did.

PS: You deal with extreme cold in the Northwest Territories. What sort of technical challenges do you deal with to get the shot?

PK: Well, I get this question a lot and the truth is that shooting in the cold sucks but is also kind of invigorating and exciting. The main problem is with batteries, they die so fast when you are shooting video, in particular. I use a Nikon D810 for stills and I find those batteries to be great. During the assignment, we were in the midst of a cold snap where it dropped to -40° Celsius (ed: equivalent to -40° F) almost everyday. My shutter would freeze and batteries on the Sony died constantly. The only way to really deal with that is to put the body of your camera inside your parka when not shooting and to keep warm batteries close by.

Here’s a little secret about the Arctic and Northern regions of the world…there is always a warm shelter nearby. People think we’re walking around in -40° for hours on end, which isn’t the case at all, we’re not crazy! So the trick is just to put your batteries inside, go out and shoot for a little bit, warm up again, go shoot a little more and so on. The only real problem I had with the cold was when I was shooting the aurora borealis. I was usually doing a timelapse on my Nikon, which you have to leave on a tripod for about 30 minutes. The camera would completely freeze after about 15 or 20 minutes and sometimes the camera just stopped taking pictures. It was frustrating and a bit disheartening when that happened but thankfully I was shooting video at the same time so it wasn’t a total bust.

PS: There’s been on-going discussion in the world of photojournalism around the limits of “parachuting in” to cover a story. On the one hand, a non-local can offer a “fresh” perspective. On the other hand, they might not capture the essence of a place. You’ve covered large swaths of the NT including many different indigenous populations. I wonder if you could share your thoughts about this.

PK: I’m really happy you asked this question because it’s an important one. I think anyone who says that non-locals offer a fresh perspective is only trying to justify parachute journalism; it’s a cop-out. If this idea of a “fresh perspective by a non-local” were true, why aren’t editors hiring people from Alaska or Michigan or Idaho or Ethiopia or Korea or Pakistan or anywhere else to do stories about New York or Los Angeles or Washington? That would be a fresh perspective I’d love to see. Furthermore, I don’t think the perspectives, especially about Indigenous people, are fresh at all, quite the opposite actually. We’ve seen the same images, tropes and cliches used time and time again since the invention of the camera.

But I think this conversation is about much more than parachute journalism – this is about power structures and privilege. Historically, the camera has been a tool of colonization and white supremacy and classism and sexism. You see it in archival photographs across the world where images of Indigenous, Black, Asian and other non-white people are displayed in museums and magazines as exotic people from far away lands whose names were never attributed, staring blankly at a wealthy white man holding a strange box. That still exists today. The narratives and images that we consume are still written and photographed primarily by people without connection to the places and people they are photographing. So really, the issue isn’t about offering fresh perspectives, it is about giving people the power to shape their own stories.

As far as I know, I am the only photographer in the history of the Northwest Territories to have been assigned a story about the Northwest Territories by The New York Times…and the Times has been doing stories about this place for decades. That is absolutely crazy to me. But there are tens of thousands of photographers around the world who have never had the opportunity to cover their own communities or regions for a major publication, and it is not because they are not talented. This is why I try my best to give back and offer mentorships and opportunities to other visual storytellers in my region, because I don’t want to be the only journalist in the Northwest Territories who did this. There are so many talented writers and photographers and artists and storytellers here that all deserve these chances.

I also think it’s important to note that we’re not asking people to stay out or not cover our regions. We want and need journalists to do stories but we also want them to do good work that represents people accurately, and we need them to be allies who help develop our skills and vouch for other photographers and journalists. Daniella Zalcman is a photographer who does this extremely well. She tells stories about Indigenous communities but she also works incredibly hard to advocate for female and non-binary photographers and Indigenous photojournalists, including myself. Daniella is just one shining example in a movement toward better representation and tearing down these colonial and sexist constructs in our field. When I was offered the chance to work with The New York Times, some people asked if I was worried they would get it wrong and I said no because I believed it was my job to make sure it was right. I really must applaud the editors for not just giving me an opportunity to do such a huge multimedia piece as a first assignment, which is kind of unheard of, but for being so open-minded and caring to my perspective as a local. Their trust in me made the story that much more robust (and accurate), and it was a wonderful, collaborative experience that I’m proud of. By having these conversations and giving people like me a shot, our photo industry and media landscape is only getting better.

All photos copyright Pat Kane and used with permission.