Share

A Student Plagiarized an African Artist. Then His Work Was Exhibited at the Milan Photo Festival.

In 2014, curator Simon Njami engaged Ethiopian artist photographer Aïda Muluneh to interpret Dante’s Inferno for an exhibition at the Smithsonia...

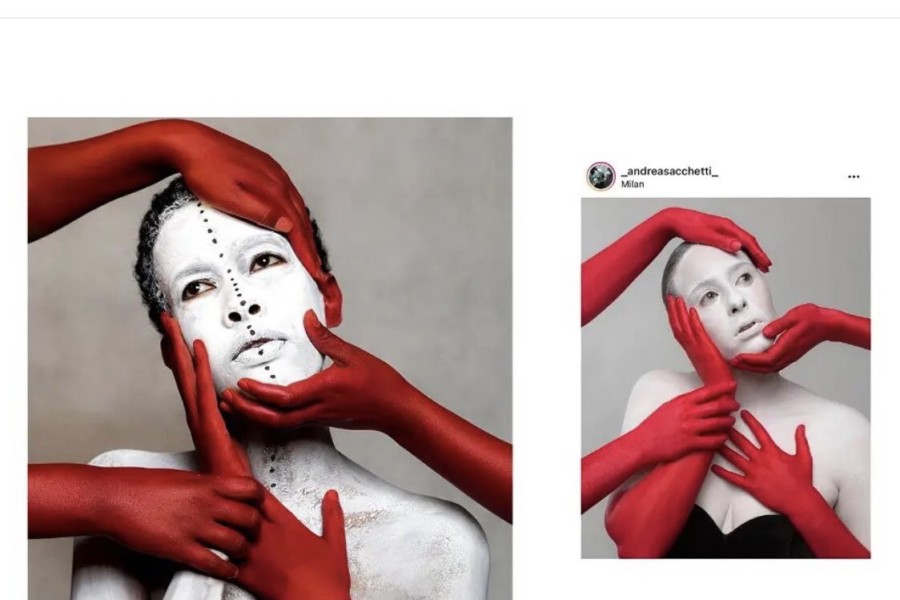

In 2014, curator Simon Njami engaged Ethiopian artist photographer Aïda Muluneh to interpret Dante’s Inferno for an exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art entitled The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Purgatory, and Hell Revisited by Contemporary African Artists. Muluneh’s “The 99 Series” featured a model set against a light grey mottled background, with her body and face covered in white paint, and her hands dipped in red.

In this episode of the PhotoShelter podcast Vision Slightly Blurred, Sarah Jacobs and Allen Murabayashi discuss the plagiarism of Aïda Muluneh’s work.

In arguably the most iconic image, the model places her left hand against her cheek and her right hand on her chest, while three other red hands extend from outside the frame to grasp the model at various points. The model’s head tilts slightly and her gaze extends far off into the distance. The image is contrasty, vibrant, and visually arresting. In her artist statement, Muluneh describes her Inferno as “the gray existence” of her country’s past, but also of our individual pain.

On Twitter, the African Women in Photography account noticed a far too similar image created by an Italian photo student, Andrea Sacchetti, which was a part of a group exhibition at the 2021 Milan Photo Festival.

The Istituto Italiano Fotografia assigned students to interpret Dante’s Inferno, and Sacchetti indisputably plagiarized Muluneh without attribution nor permission, producing a series of diptychs that used a model painted in white with red hands, photographed against a gray background. Sacchetti’s images lack both an emotional intensity and technical excellence (i.e. lower contrast, less deftly styled hand position, vacant gaze) of Muluneh’s original.

After hundreds of retweets, the Festival issued a statement on their Instagram account, acknowledging the “identical” image. However, they further state that “there was no will to plagiarize against such a prestigious author and we know that the young photographer has already apologized to the author.”

The history of art and photography is filled with accusations of plagiarism. In recent times, the late Ren Hang was accused of plagiarizing the work of Ryan McGinley, Guy Bourdin, Robert Farber and Robert Mapplethorpe. Iranian photographer Solmaz Daryani accused the German photographer Maximillian Mann of copying her work from Lake Urmia. But while specific images in those cases have either similar poses or similar scenes, none of the images share a level of identicality as Sacchetti’s plagiarism of Muluneh.

In the U.S., copyright law doesn’t allow creators to copyright a concept. And photographers have had limited success in leveraging copyright in cases of visual plagiarism. But that doesn’t mean the individuals shouldn’t push back against blatant instances.

In all art forms, imitation provides a methodology for learning. Jazz students often transcribe Charlie Parker solos, learning not only the notes, but the phrasing and subtle shifts in timing that elevate Parker’s playing. And in photography, it’s very common for students to replicate photos they admire to deconstruct lighting patterns, lens selection, etc.

But it is the height of privilege for a student who commits plagiarism against a famous African artist to have the continued support of a significant European photo festival. The continued exhibition of Sacchetti’s work gives tacit approval to others to commit the same infraction without consequence.

At a moment in history when there is heightened awareness of uncredited appropriation from Black creators, this outcome is a sad commentary on the Milan Photo Festival’s attitude towards plagiarism and more specifically against the moral rights of an African artist.

Muluneh, the founder of the Addis Foto Fest, shared her thoughts through the organization’s Twitter account, stating in part:

“I take this quite personally, not just for me, but imagine for other photographers and artists who nobody knows, or who are trying to come up, who face the similar challenges….It’s still a conversation that needs to continue. Just because there’s been one post shared and a couple of messages sent, it’s not the end of the conversation.”