Share

The Moral Imperative to Photograph Race Accurately and Authentically

Did you catch Google’s Super Bowl ad promoting Real Tone, a new camera technology designed to more accurately highlight the nuances of diverse...

Did you catch Google’s Super Bowl ad promoting Real Tone, a new camera technology designed to more accurately highlight the nuances of diverse skin tones?

With technological advances like Real Tone and efforts to more authentically photograph Black and brown skin, as well as increased discussions around using things like color grading to accurately edit photos, one might think we’re further from the days of the problematic Shirley card than we really are.

Just this week I stumbled across a tweet by NFL cornerback Prince Amukamara that moved me to throw my phone across my living room. In the photo, Prince, who is Black, is pictured between two white men and is nearly invisible except for his inaccurately lit, overly saturated mouth and teeth. The caption reads, “I promise you I’m in this picture… .” While some well-meaning Twitter fans responded with edits where they “fixed” the exposure issue, the problem is so much deeper than that.

Aundre Larrow, a videographer, director and photographer known for speaking out about equity in the photo industry tweeted, “I am begging camera, editing and phone companies, please do better. Fix your metering, make your flash extend further and be softer. This can’t keep happening.” He’s right.

But before we all jump headfirst into the current technological deficiencies or advances many of us are so excited about, it’s imperative we start with our lens way back. We need to remember that photography has a dark history of exerting oppressive control on marginalized communities. So before we discuss proper lighting setups for people with Black and brown skin, or how to edit skin tones accurately in post processing, spend some time doing work that doesn’t require a camera. It involves education.

“It is imperative to think about the ethics around producing and disseminating photographs. We must be truthful about the harm caused by the hierarchical relationship between photographer and sitter, by the intersection of that relationship with racism and sexism. We must recognize the social effects of our photographs. Only then can we begin to use photography as a tool for empowerment rather than a tool that enacts its own violence,” New York-based documentary photographer Laylah Amatullah Barrayn writes.

The following essay was written by the very talented Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, a documentary and portrait photographer based in New York City whose work has been published in Vogue, The New York Times, The Washington Post, NPR, BBC and National Geographic. In addition to her photography work, she’s given talks at Yale University, Harvard University, The International Center of Photography, Tate Modern London, Rochester Institute of Technology, World Press Photo and The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

It’s one of the many meaningful essays outlining the importance of inclusive photographic practices featured in The Photographer’s Guide to Inclusive Photography, a free educational guide we made in partnership with our friends at The Authority Collective.

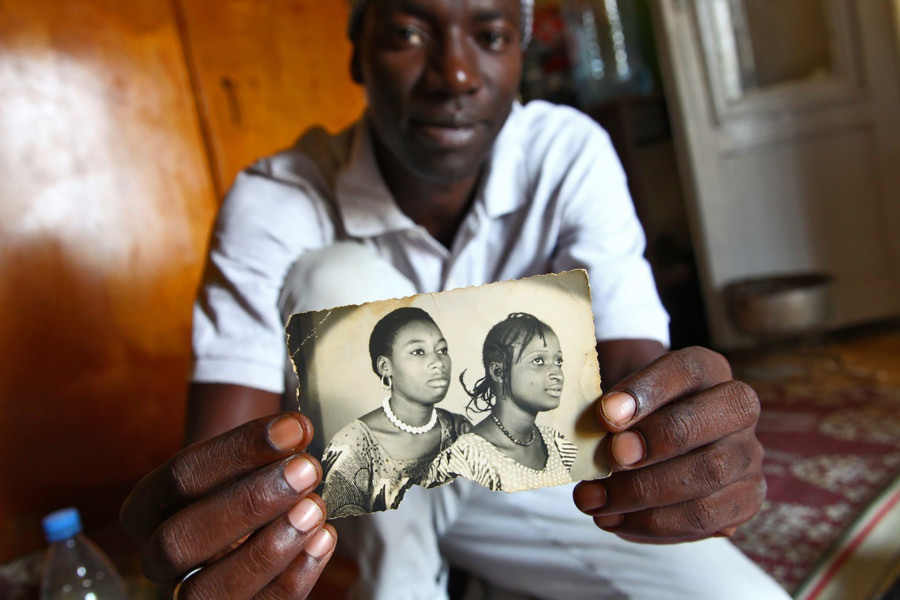

Cover image by Laylah Amatullah Barrayn.

A young woman with microbraids pulled back into a ponytail that balanced on the nape of her neck demanded of me, “No poste!” She couldn’t have been more than twenty-five years old. Her hands shielded her face against my lens that was aimed and ready to receive her likeness for my memory. Her dress, an empire-waisted gown sewn from stiff bazin, was the focus of my interest. It was beautiful, distinct and emblematic of Senegalese style. For me, it was a moment worthy of a photograph. Her reply to my gesture, which meant to inquire for permission – “no poste!” was disappointing but her enacting her agency in the face of a camera was not.

This encounter was among my first visits to Saint-Louis, the former colonial capital of Senegal, many years ago. During subsequent sojourns, readings and conversations with people like local Senegalese archivists and photographers Ibrahima Thiam and Adama Sylla, I’ve come to learn of the complicated relationship between Black bodies and photography. SaintLouis, otherwise known by its proper Indigenous name, Ndar, acted as the base for photographers who took up photomaking as a colonial project. That legacy lives on. Nearly one hundred years before I visited Saint-Louis, photographers like Pierre Tacher and François-Edmond Fortier documented the burgeoning federation of states then known as Afrique Occidentale Française (French West Africa). Many images of the Senegalese and adjacent populations were produced, printed as postcards and distributed in France and other global destinations. This distribution of photographs was done with the very specific agenda of justifying the subjugation of colonialism. There are moments that can trigger a collective memory of that trauma — like the sight of a foreigner holding a camera.

As we seek to indigenize or de-colonize our practice in photo-making, archiving, and other forms of documenting, it is imperative to evaluate how we perceive other humans. It is crucial to be honest about how much we have internalized the racist ideologies that have become deeply ingrained in our societies everywhere in the world. Part of uncovering that truth is to be present, to listen and be open to what is revealed during efforts to challenge problematic tropes and projects. It is work to be taken up specifically if one has benefitted from racist structures, policies, and institutions. It’s personal work. It’s difficult and most importantly, it is a task for the courageous. This work benefits everyone. Racism is violent, limiting, and unnatural. This self-reflection makes all the difference in moving the conversation forward. Believing that one group is the prototype of the human form limits us all. When photographers stand in the space of racial hierarchy and fail to see the humanity in their fellow humans — one can’t humanize another human, nor give a voice to someone who already has one — we fail as a society.

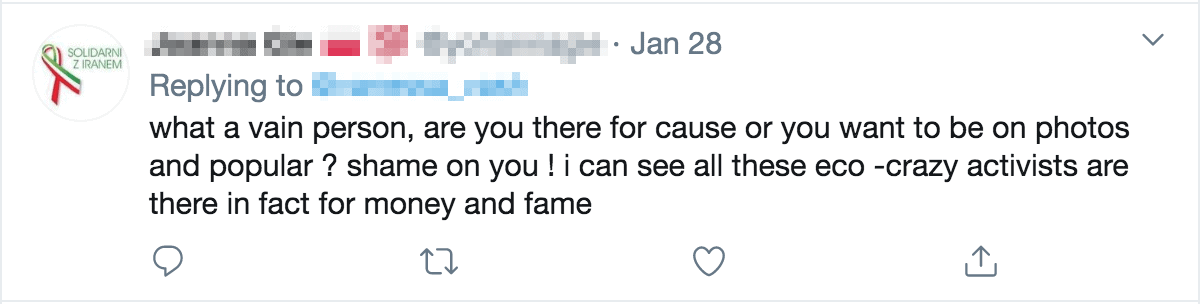

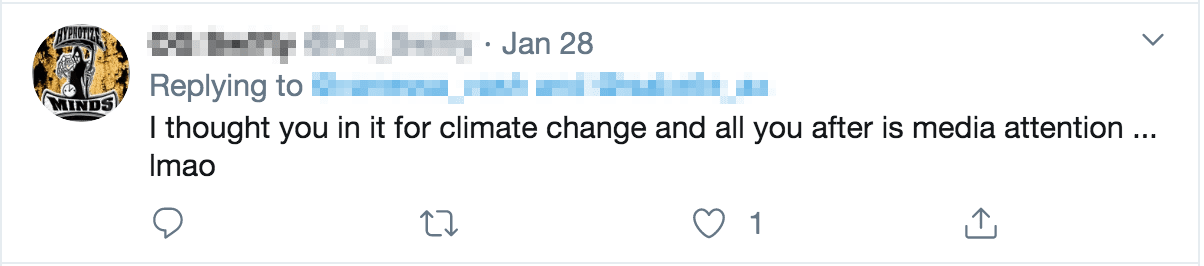

I think of the relatively recent incident where a young Ugandan climate change activist was cropped out of an AP wire photo. Vanessa Nakate posed for a photo with four other young activists, who all were white — Greta Thunberg, Isabelle Axelsson, Luisa Neubauer and Loukina Tille — and she was cut out. It was a devastating act of erasure surely predicated on race. Why else commit such an unethical gesture? The commentary online varied from pointing out the obvious racial undertones to a host of excuses feigning that the cropping was an honest mistake. It all speaks to the idea of visuality, meaning what influences our sight, what determines how and what we see. In this case, a photo editor made a decision to promote a one-dimensional narrative of who is allowed to be a champion of climate activism. The inclusion of a Ugandan activist would have disrupted the ongoing narrative of Africans and peoples of African descent as not being agents of change when that narrative is not only false, but dangerously limiting.

I look to the scholarship of Dr. Deborah Willis who has authored over 30 books on Black visual culture and photography. Her seminal book, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers, 1840 to the Present was the first comprehensive book published on Black photographers and should be included in all photographic curricula internationally. In this text, Dr. Willis chronicles and offers an analysis of Black photographers such as Jules Lion, James Presley Ball and Augustus Washington who all have had photo practices since the inception of the first viable photographic process, the daguerreotype by Louis Daguerre in 1840. Not to mention the visual activism of Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth who turned the camera on themselves as an act of liberation.

Sociologist W.E.B Dubois pushed back against the negative imagery of people of African descent and the racist science that was prevalent during the late 1800s and early 1900s through his scholarship and usage of photography. His seminal exhibition at the Paris Exposition in 1900 is a prime example of his efforts. W.E.B Dubois assembled approximately 363 images, graphs and other visual materials, depicting the lives of Black Americans living in and around Atlanta, Georgia. Fifty million visitors viewed the Exposition des Nègres d’Amerique at the fair that ran from April to November. He once asked in the Opinion column of the Crisis magazine, “Why do not more young colored men and women take up photography as a career? He continues, “The average white photographer does not know how to deal with colored skins and having neither sense of the delicate beauty or tone nor will to learn, he makes a horrible botch of portraying them.” W.E.B Dubois understood the power of photography and the importance of authorship and agency. And 100 years later, we are still grappling with doing right in the usage of the camera.

In order to create a new world, one must first be able to envision it. It is imperative to think about the ethics around producing and disseminating photographs. We must be truthful about the harm caused by the hierarchical relationship between photographer and sitter, by the intersection of that relationship with racism and sexism. We must recognize the social effects of our photographs. Only then can we begin to use photography as a tool for empowerment rather than a tool that enacts its own violence.

Additional resources:

- The Photographer’s Guide to Inclusive Photography

- Neeta Satam, “The Ethics of Seeing”

- Edwin Martinez, “Navigating the River: The Hidden Colonialism of Documentary”

- April Zhu, “What Would Photography Look Like If It Were Actually Inclusive?”

- Clary Estes, “The Colonialism of Photojournalism”

- Seattle Times’ Guidelines for Inclusive Journalism

- Decolonizing Documentary & Journalism Reading List by Ligaiya Romero

- Everyday Africa’s Exhibition Guidelines